| Kahaym Kahaym grem | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Fusional | ||||||||||||

| Alignment | Nominative-accusative | ||||||||||||

| Head direction | Initial | ||||||||||||

| Tonal | No | ||||||||||||

| Declensions | Yes | ||||||||||||

| Conjugations | Yes | ||||||||||||

| Genders | Two (Common, Neuter) | ||||||||||||

| Nouns decline according to... | |||||||||||||

| Case | Number | ||||||||||||

| Definiteness | Gender | ||||||||||||

| Verbs conjugate according to... | |||||||||||||

| Voice | Mood | ||||||||||||

| Person | Number | ||||||||||||

| Tense | Aspect | ||||||||||||

| Meta-information | |||||||||||||

| Progress | 96% | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Creator | Mattia Tosin | ||||||||||||

The Kahaym language (Kahaym grem, sometimes also called Nilgrem, language of men, Mehndeilgrem, language of Mehndeil, or Evriirgrem, language of the Empire) is spoken almost all over the continent of Kahaymah, but officially recognized as national language only in the territory of the Imperial Union of Kahaymah and in Hevera.

Classification and Dialects[]

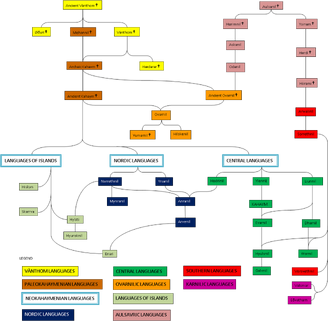

Classification of the most important Nil languages of Kahaymah.

The Kahaym language belongs to the Nil languages group (or human languages) and is part of the Central Neokahaymenian languages. It comes from the Ancient Kahaym and it is the most releated to this old language, now extinct.

As Kahaym is spoken everywhere in Kahaymah, it has been influenced by other languages spoken in the lands out of the Galedarvaar. So more and more dialects were born, and in some cases it is still evolving a new dialect. For example, when Kahaym spread across the land of Hakhiir, the Hakhiiric dialect has started setting up. The pronunciation is what has changed most: the Halkars (race of humanoid cats) cannot pronunce some sounds like /u/ or /l/, so the pronunciation of some words before and the alphabet then have changed a lot. Furthermore, some words of the native languages entered in the spoken Kahaym; for example, if we consider Heveranish dialect we can hear words like kasir, stronghold (vranastir in Kahaym) or holden, world (herdrain in Kahaym).

Phonology[]

These are the sounds which can be found in the Galedaric/Ylennil version of Kahaym. Other dialects could have different sounds, expecially for vowels.

Consonants[]

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ | /ɱ/ | /n/ | ||||||||

| Plosive | /p/ /pʰ/ /b/ | /t/ /d/ | /ʈ/ | /c/ | /k/ /g/ | ||||||

| Fricative | /f/ /v/ | /s/ /z/ | /ʃ/ /ʒ/ | /χ/ | |||||||

| Affricate | /t͡s/ | /t͡ʃ/ /d͡ʒ/ | /ħ/ | ||||||||

| Approximant | /ʋ/ | /θ̞/ /ð/ | /ɹ/ | /j/ | /h/ | ||||||

| Flap or tap | /ɾ/ | ||||||||||

| Lateral app. | /l/ /lʰ/ |

- Some sounds are composed by a letter followed by "h". This letter alters the pronunciation of some consonants more than all the other letters. For example: vh /ʋ/; dh /ð/; th /θ̞/...

Vowels[]

| Front | Near-front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | /i/ /y/ | /ɨ/ | /u/ /ɯ/ | |

| Near-close | /ɪ/ | |||

| Close-mid | /e/ | /o/ | ||

| Mid | /ə/ | |||

| Open-mid | /ε/ | /ɔ/ | ||

| Near-open | /æ/ | |||

| Open | /a/ | /ɑ/ |

- Vowel "a" can change its pronunciation with letter "h". For example: ah /ɑ/ or /ə/. Kahaymah ['kɑaym'ɑ], Kahaymah.

Writing System[]

Kahaym language uses the same alphabet as English. In Ancient Kahaym, there were two different writing systems: the Vànthom and the Runic. They were completely different from the modern alphabet and they had a lot of characters (every sound had its own symbol). As the alphabet was deemed a holy thing so only priests and nobles were allowed to learn writing, at the end of the First Era some plebians started using an invented alphabet, which they called Mehayllerdrkon, the "people's voice" in Vulgar Ancient Kahaym (very similar to the modern Ovarnil alphabet). Soon it spread and at the beginning of the Second Era replaced the old alphabet.

Official Alphabet (Kahaymsyrdrin)[]

These are all the letters recognized by all Kahaym's dialects and all the letters belonging to the Galedaric/Ylennil dialect.

| Letter | Name | Sound | Followed by "h" |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | an | /a/, /ɑ/ or /æ/. Rarely /ə/ | /ɑ/ or /ə/ |

| B | bet | /b/ | no change |

| C | cet/ket | /k/, /s/. Rarely /c/ | /t͡ʃ/ or rarely /χ/ |

| D | dan | /d/ | /ð/ |

| E | e | /ε/ or /e/ | no change |

| F | fen | /f/ | no change |

| G | gan | /g/ | /j/ |

| H | hol | mute, /ħ/ or /h/ | does not exist |

| I | i | /i/ or /ɪ/ | no change |

| J | jaun | /ɨ/, rarely /ʒ/ or /d͡ʒ/ | no change |

| K | kyel | /k/ | /c/ or /χ/ |

| L | leat | /l/ | /lʰ/ |

| M | man | /m/ or /ɱ/ | no change |

| N | nan | /n/ or /ɱ/ | no change |

| O | on | /o/ or /ɔ/ | no change |

| P | pev | /p/ | /pʰ/ |

| Q | quit | normally /k/ | no change |

| R | ros | /ɾ/ or rarely /ɹ/ | no change |

| S | sen | /s/ | /ʃ/ |

| T | te | /t/ or /ʈ/ | /θ̞/ |

| U | un | /u/ or /ɯ/ | no change |

| V | vot | /v/ or /ʋ/ | /ʋ/ |

| W | wer | /ʋ/ or /ɯ/ | no change |

| X | xet | /ks/ | no change |

| Y | yaln | /y/ | does not exist |

| Z | zet | /z/ or /t͡s/ | no change |

- The letters C, J, Q, W, X, Z are not present in original Kahaym words. They appear just in foreign words.

- T is pronunced /ʈ/ especially when followed by another T.

- M and N are pronunced /ɱ/ especially when are followed by another labio-dental cononant.

- When C is followed by H it sounds like /χ/ only in a few words from foreign languages or from Ancient Kahaym.

- Some letters like B, D, F, G, H, P cannot get doubled like the others (C, J, Q, W, X, Z excluded).

- Usually letters' pronunciation changes according to the specific word, like in English.

- Diphthongs like AE, EA, OU, OO, EE... are always pronunced articulating each vowel. So, for example, AE is pronunced [aε] or [ae], OO is pronunced [oː] and not [uː].

Extended Alphabet (Kahaymalsyrin)[]

In addiction to the other letters, in some versions of Kahaym are used other letters for adapting certain sounds which are not present in the Kahaymsyrdrin or for summarizing some consonants' groups (for example: th becomes Þ).

| Letter | Name | Sound | Replaces | Country(ies) where it is used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Æ | æns | /æ/ or /æɪ/ | "A", "AE" and "EI" | Myrrinel, Anraloth |

| Å | åls | /ɔ/ or /ɒ/ | open "O" | Myrrinel, Hastar |

| Ð | ðwir/ðor | /ð/ | "DH" | Anraloth, Hevera, Worlan, Galver |

| Č | čen/čakk | /tʃ/ | "CH" | Hevera, Galver |

| Ğ | ğirs | /ʤ/ | "J" (rarely) | Hevera, Galver |

| Ł | łeun | /lʰ/ | "LH" (rarely) | Anraloth, Hedrior, Hevera, Kyliun, Liun, Worlan, Galver |

| Ø | ørsen | /ø/ | nothing | Myrrinel |

| Š | šen | /ʃ/ | "SH" | Hevera, Galver |

| Þ | þet | /θ/ | "TH" | Anraloth, Hevera, Galver |

- These letters don't always substitute the groups of letters in "Replace" column; they are more often used as "additional characters" for the original alphabet.

Grammar[]

In Kahaym there are two genders (common and neutral) and two numbers (singular and plural). Nouns don't change according to the context very much, because they aren't declined according to case.

Personal Pronouns[]

In Kahaym language, nouns are not declined according to case, except for personal pronouns. They conserve four of the ten cases in Ancient Kahaym (actually every pronoun is declined three times, because dative and accusative coincide).

| Nominative | Genitive | Dative-Accusative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | riil/ril | riis/ris | riim/rim |

| 2nd signular | lus/luhs | lur/luhr (archaic: luhen) | lum/luhm |

| 3rd signular male | hem | hes | hemn/hemmen |

| 3rd singular female | him | his | himn/himmen |

| 3rd singular neutral | eld | els | eld |

| 3rd signular generalized | naal/nal | naas/nas | naam/nam |

| 3rd singular polite form | Nel | Nes | Nem |

| 1st plural | raan | raas | raam |

| 2nd plural | dien | dies | diem |

| 3rd plural common | hiald | hials | hialm |

| 3rd plural neutral | hiern | hies | hiern |

| 3rd plural generalized | hiald | hials | hialm |

- In Kahaym, possessive adjectives are the same as the genitive of personal pronouns.

- The generalized form can be used for everything, irrespective of the gender. They are frequently used in the spoken language for animals and things (for people, you have to use male/female/common pronouns). They are used especially in questions and riddles where you don't know what you are refering to.

- Note: the 3rd singular person in the polite form, in nominative, it is not just the polite form of you, but it means also god/goddess in Kahaym.

- In Kahaym language, if you want to say my self, you just use the dative case. Self is never used with pronouns, although there is a word, nilran, which has more or less the same meaning.

Distinction of the gender[]

In Kahaym there are two genders: common and neutral. Tell apart the two genders is quite easy, but sometimes could be difficult for someone who doesn't know anything about Kahaymenian culture.

Common nouns. Common nouns are all nouns relating to life. They are names of humans, animals and plants and the elements of Kahaym (actually, Kahaym is an acrostic. Its letters are the starting-letters of the names of six gods, called the Gods of Kahaym: they are Kaan, God of Fire, Anyr, Goddess of Air, Hammern, Goddess of Water, Alyun, God of Soil, Ynnel, Goddess of Light and Murrnahr, God of Darkness. All these elements combined are the Kahaym, a word from the Vànthom language which means "life", "soul", "good ealth" and "gold"). Common nouns are also the emotions and whatever a living being can be in its life.

- In summary living beings and what is related to life, fire, air, water, soil, light, darkness, Kahaym (with all its meanings), emotions and most of the characteristics of a living being are common (even gremen, dead, is common, but not gremlast, death, which is neutral).

Neutral nouns. Neutral nouns are all nouns relating to inanimated things. They are all the tangible objects with no life and abstract concepts which not relate to life. In fact, feelings are typical of living beings so they are common; for other nouns is the same reasoning.

Nouns[]

Nouns decline according to the two numbers (singular and plural). If we want to build the plural, we have to put -ar at the end of the word in singular.

| English | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| dog | hynin | hyninar |

| man (human) | nil | nilar |

| girl | dhreyman | dhreymanar |

| water | hammern | hammernar |

| god | nel | nelar |

| tear | dhorma | dhormaar |

- As you can see in tear, if the word ends with a vowel (even if it is A) you just put -ar without removing the previous vowel.

Exceptions[]

But there are some exceptions: in fact the noun at the plural form can change in three different situations.

Neutral gender, consonant ending. If the noun is neutral and ends with a consonant, this one is eliminated and replaced by another one, then -ar is addicted. There are no rules that tell us which letter replaces the last one, so you must learn it by heart (but you can be sure this letter will be D, G, K, L, N, S, T or V. The most common are L and V).

| English | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| emotion | frir | frilar |

| mountain | hel | hegar |

| acrostic | raadstarn | raadstarlar |

| culture | dhrenur | dhrenuvar |

| shore | lyumiln | lyumilvar |

| island | lynorm | lynorvar |

Common gender, "-r" ending. If the noun is common and ends with -r, this letter makes way for n and then -ar is addicted.

| English | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| people | vriir | vriinar |

| queen | kayver | kayvenar |

| elder | dhrelor | dhrelonar |

| traveller | viedror | viedronar |

| element (of the creation) | hiladvir | hiladvinar |

| living creature | hiror | hironar |

Double-consonant ending. If the noun (common or neutral) ends with two same consonants (for example, -rr or -nn...), the last one makes way for v and then -ar is addicted.

| English | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| friend | nirsenn | nirsenvar |

| snow | nyll | nylvar |

| city | dayrr | dayrvar |

| bridge | sirtrann | sirtranvar |

| horse |

hersenn |

hersenvar |

| Dhurloss (dragon race, now extinct) | Dhurloss | Dhurlosvar |

Articles[]

There are just two articles: determinative (en) and indeterminative (et). Articles are put before the noun and before all its adjectives, but never appear when there are possessive and numeral adjectives. Although it is necessary to say that actually there are no clear rules for determinating the positioning of the article. This is because of the influences of Ancient Kahaym with Nordic languages and Aulsavric languages.

Verbs[]

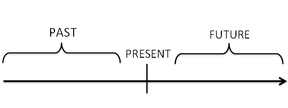

Kahaym language has not a 'timeline' for verbs, but time is divided in three different tied points.

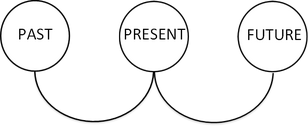

Typical 'timeline' of a language like English.

Verbs are not conjugated according to the person, so it is necessary to explicate the subject. There are two main groups of verb tenses: simple moods and composed moods.

In Kahaym you have to imagine not at a timeline like in English, but at three distincted points in the time. In Kahaym there is not the concept of a continued line, but more simply what happened in the past is in the past and the same for the future. It means that Kahaymenians don't tell apart the actions which happened yesterday and what happened ten years ago.

As an example, here will be used the verbs hind, eat, and dhremna, cry.

Simple moods[]

The simple moods are made of just one part. That's why they are called "simple".

Indicative[]

Indicative is the mood of certainty: it is used to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentences. There are three tenses in it: present, perfect and future. Present is used for habits or actions which are true now. Perfect is used for actions in the past which now are over. Future is of course used for actions which will happen in the future.

| Present indicative | base form | hind

dhremna |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect indicative | consonant ending: -et

vowel ending: -t |

hindet

dhremnat |

| Future indicative | consonant ending: -ur

vowel ending: -r |

hindur

dhremnar |

Imperative[]

Imperative is a mood used to command something. It has just one tense, the present and it is made by the base form of the verb. If the verb ends with a vowel, the vowel is eliminated. For example: hind!, eat!; dhremn!, cry!.

Participle[]

There are two tenses: present and past. The present can be translated as a relative clause, with active meaning and expressing the state of being contemporary. The past is the same, but has a passive meaning and expresses antecedence.

| Present participle | consonant ending: -ind

vowel ending:-nd |

hindind

dhremnand |

|---|---|---|

| Past participle | consonant ending: -it

vowel ending: -t |

hindit

dhremnat |

Composed moods[]

As the name says, composed moods are composed by more than a part.

Infinitive[]

The infinitive, used in particular syntaxes, is made by the preposition den (similar to to) and the base form of the verb. For example: den hind, to eat; den dhremna, to cry.

Progressive[]

It describes actions in progress in three times: present, perfect and future.

| Present progressive | consonant ending: ir + -ard

vowel ending: ir + -rd |

ir hindard

ir dhremnard |

|---|---|---|

| Past progressive | consonant ending: irn + -ard

vowel ending: irn + -rd |

irn hindard

irn dhremnard |

| Future progressive | consonant ending: irld + -ard

vowel ending: irld + -rd |

irld hindard

irld dhremnard |

- Ir, irn and irld are respectively the indicative present, perfect and future of the verb tarn, be.

Conditional[]

The conditional mood is used for speaking of an event whose realization is dependent upon another condition. It is used in conditional sentences which are divided in three groups: reality (zero conditional in English), unreality (first conditional) and impossibility (second and third conditional). For the formation of the conditional sentence, look at Syntax.

| Present conditional | thil + past participle | thil hindit

thil dhremnat |

|---|---|---|

| Past conditional | thald + past participle | thald hindit

thald dhremnat |

| Future conditional | tharn + past participle | tharn hindit

tharn dhremnat |

Colligative[]

The colligative mood is used to connect the three point in the time (past, present and future; from Latin: colligo, connect). There are two times: past-present and future-present. They are used to describe actions which happen in the past and now aren't over yet and actions which happen now and will continue in the future (in part like the future imperative in Latin).

| Past-present | Consonant ending: nart + -uld

Vowel ending: nart + -ld |

nart hinduld

nart dhremnald |

|---|---|---|

| Future-present | Consonant ending: narr + -uld

Vowel ending: narr + -ld |

narr hinduld

narr dhremnald |

- Nart and narr are respectively the indicative perfect and future of the verb ner, have.

Generalized future[]

The generalized future has the same meaning of the future indicative, but it is composed by two parts: the verb at present indicative and the word grann at the end of the clause (from the Ancient Kahaym, locative of gor, future). For example: riil yln (present) lum drelot grann, I'll see you in this place.

Irregular verbs[]

In Kahaym language there are some irregular verbs. What changes is the root, but desinence is often the same of regular verbs ending with vowel (even if the verb ends with a consonant; just a few verbs have a vowel-ending suffix).

Irregular verbs change their root three times in all the conjugation, so there are three different roots:

- first root: it is the base form, used in present indicative, imperative, infinitive and generalized future.

- second root: it is used for making the perfect and future indicative, past participle and conditional tenses.

- third root: it is used for present participle, the progressive mood and the colligative mood.

The paradigm of a Kahaymenian verb is composed of three tenses: present indicative, past participle and present participle. Here is, as an example, the conjugation of ner, nart, nornd, have.

| Indicative | Present: ner

Perfect: nart Future: narr |

|---|---|

| Imperative | ner |

| Participle | Present: nornd

Past: nart |

| Infinitive | den ner |

| Progressive | Present: ir norrd

Past: irn norrd Future: irld norrd |

| Conditional | Present: thil nart

Past: thald nart Future: tharn nart |

| Colligative | Past-present: nart norld

Future-present: narr norld |

| Generalized future | ... ner ... grann |

The verb tarn, be/become is more complicated and has its own conjugation.

| Indicative | Present: ir

Perfect: irn Future: irld |

|---|---|

| Imperative | ir |

| Participle | Present: derland

Past: dernt |

| Infinitive | den tarn |

| Progressive | Present: ir derland

Past: irn derland Future: irld derland |

| Conditional | Present: thil dernt

Past: thald dernt Future: tharn dernt |

| Colligative | Past-present: nart dernt

Future-present: narr dernt |

| Generalized future | ... ir ... grann |

Formation of passive voice[]

Making the passive voice is very simple: you just have to put the past participle of the verb tarn after the verb. For example: kam, call -> kam dernt, be called; gar, leave -> gar dernt, be left.

"Absolute negation"[]

Kahaym language has a particular way to express a concept: if we consider a word (it can be anything we want: a noun, an adjective, an adverb...), we can state its opposite meaning just putting haa- before the word. This is a particular particle which comes directly from the Vànthom language. There were a lot of prefixes and suffixes for giving a meaning to a word, like tas-, used to say that this word isn't actually true or it is an example. But the most known among humans in Kahaymah are -nil, which expresses that something is related to humans, and -ah, a suffix used for naming countries (Kahaymah, in fact, is Kahaym-ah, the land of Kahaym).

When we use the "absolute negation" with the particle haa-, also called vrinskond haaviimar, we obtain a word with an opposed meaning. For example: viimar, reality -> haaviimar, falseness/ negation; vrin, everything -> haavrin, nothing; vraad, always -> haavraad, never; sken, can -> haasken, cannot.

Remember that when particle haa- is added to a word which starts with A, this first letter is eliminated: aver, like -> haaver, not like.

Comparison[]

In Kahaym there are three degrees of comparison (like in English): positive, comparative and superlative. Positive just denotes a property:

- Garnon ir vrast, John is tall;

- Idhrial irn hirvrin an tark, Idhrial was heroic and brave.

Comparative[]

- Riil ir vrastven luhm, I'm taller than you;

- Myrrinel ir nemnven Liun, Myrrinel is bigger than Liun.

Comparative is simply made of the full adjective and -ven put at the end and the following noun (if it is a pronoun) in accusative case. In Kahaym there is only a greater degree, but if we want to give a meaning of equivalence or a lesser degree we must use different constructions.

To express an equivalence meaning we use a positive degree of comparison, but we put aver (like) in the middle. For example:

- Riil ir vrast aver luhm, I'm as tall as you (lit. I'm tall like you);

- Kayn Idhrial ir drannlin aver Evrior Menhdeil, King Idhrial is as famous as Emperor Menhdeil;

- Liun (haair nemn aver)/(ir haanemn aver)/(ir nemn haaver) Myrrinel, Liun isn't as big as Myrrinel (all three options are allowed).

For a lesser degree we use the "absolute negation" put to an adjective in its comparative form.

- Riil ir haavrastven luhm, I'm less tall than you (lit. I'm not-taller you);

- Liun ir haanemnven Myrrinel, Liun is less big than Myrrinel.

NOTE: in this last one situation we can't say Riil haair vrastven luhm, because it is not allowed (although it is admitted in some dialects, especially Liunnilic and Evarnilic dialects).

Superlative[]

Superlative is made of the full adjective and -tar (or -ar if the adjective ends for T) put at the end. We can tell apart two types of superlative: comparative and absolute.

Comparative superlative is used when there are two or more objects considered and one of them stands out for a specific property, but we don't want to consider the others directly. It is made of superlative form preceded by the determinative article en and sometimes followed by an expression which specifies the object's belonging to a group.

- Riil ir en vrastar, I'm the tallest;

- Amyrn irn en drannlintar kayver yn Anraloth, Amyrn was the most famous queen of Anraloth.

It can be used also for emphasizing a characteristic in particular circumstances, when we already know that this characteristic (in positive degree of comparison) makes the subject stand out. For example: Hannar thil dernt en terntar nil em Hilvien, Hannar may be the most first man on Hilvien (emphasizing that no one lived on Hilvien before him).

Absolute superlative is just made of the superlative form (-tar or -ar), but it refers to one alone object which has a characteristic that is taken on an extreme level.

- Riil ir vrastar, I'm very tall;

- Syntrarlvar yn Hakhiir ir nemntar, Hakhiir deserts are extremely large.

Syntax[]

Kahaym's word order is SVO. Normally adjectives precede nouns and pronouns and adverbs follow the verb (sometimes they are at the end of the clause). There are prepositions and not postpositions.

Conditional sentences are divided in three categories: reality, unreality and impossibility. The first one is made of the present indicative in the "if" clause and the present conditional in the main clause. It expresses something which is always true. The second one is made of perfect or present indicative in the dependent clause and future conditional in the other. It states an action which is in doubt and there is no way to know if it is true or not. The impossibility expresses a concept of something that now is done, then has a result and you cannot change it. It is made of perfect indicative in the "if" clause and past or present conditional.

Example text[]

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 1[]

Vrin nilar dhrelulan em fordiim an saevorduinn derland sa yndaast an yndaastinrelar. Hiald nornd em hialm nid gannestir an mernuedtandrir vanlistan ferden hialm nid serdanvalidrartast.

- Translation: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

- Literal translation: All humans are born in freedom and equality on dignity and rights. They having in them with reason and coscience behave between them with brotherhood spirit.

- IPA transcription: [ʋɾin nil'ɑɾ 'ðɾεlulan εm foɾ'diːm an sae'vɔɾdɯɪnː 'dεɾland sa 'yndɑːst an 'yndɑːstɪnˌɾεlɑɾ ħi'ald nɔɹnd εm ħi'alɱ niːd gan'nεstiɾ an mεɾnɯe'tːændɾiɾ vɑn'listan 'fεɾden ħi'alɱ niːd ˌsεɾdanʋɑli'dɾɑɾtast]

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 2[]

Den vrin nilar en vrin yndaastinrelar an en vrin fordiinar kent em dre derland Greymsaartran gan dernt, haavrin listarin gannen, anderaver saithen, malhennon, vitharn, grem, kresilannen, vhannistardinn an ynn rilneyn, vriinneslinn aur dhrevann denviend, kaymsent, dhrelurn aur ynn heddvistonar. Drelastarem, haalistarin sa nehannen yn vhannistardinn, redistarvrennluranninn aur hilvallen heddvistor yn drenil dhrelulend alyen aur vaarden sken den braemir neyn grann.

- Translation: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs.

- Literal translation: To all humans the all rights and the all freedoms mentioned in this present Declaration are up, not-all distinction any, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political and other opinion, national or social coming, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, not-distinction on basis of political, jurisdictional or international status of anyone native land or territory can to take thought in-future.

- IPA transcription: [dεn ʋɾin nil'ɑɾ en ʋɾin 'yndɑːstɪnˌɾεlɑɾ an en ʋɾin foɾ'diːnaɾ kεnt εm dɾe 'dεɾlɑnd gɾeym'sɑːɾtɾan gan dεɾnt 'hɑːʋɾin lɪs'taɾin 'ganːεn ˌɑndεɾ'aveɾ 'saɪθ̞en ma'lʰenːɔn ʋi'θ̞aɾn grεm kɾεsɪ'lanːεn ʋanːi'stardɪnː an ynː ɾɪl'neyn vɾiː'nːεslɪnː aɯɾ 'ðɾεvanː 'dεnviεnd 'kɑymsεnt 'ðɾεluɾn aɯɾ ynː hεdːʋi'stɔnɑɾ dɾela'staɾεm hɑːlɪs'taɾin sa ne'anːεn yn ʋanːi'stardɪnː ɾedɪˌstaɾʋɾεnːlɯ'ɾanːinː aɯɾ ħil'ʋalːεn hεdː'ʋistɔɾ yn 'drεnil 'ðɾεlulεnd 'ɑlyεn aɯɾ 'vaːɾdεn sken dεn 'bɾaεmɪɾ neyn gɾanː]

Lord's Prayer[]

Raas Hedistan derland em annar,

vergren dernt Luhen nelt.

Luhen kaynrel denvieth.

Luhen rilneyn gyl dernt grann

saevern sa herdrain an annar.

Gan raam raas darsyl monn emdar,

an gar raam sa raas haamernuelar,

aver raan gar raas haamernuranvar,

an haavieth raam em haagannan

lorn fordarn raam fer grod.

[Dreir en kaynrel ir Luhen,

an en dreen, an en gladhvin,

vraadgrayn vraad.]

Amen.

- Translation:

Our Father who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come.

Thy will be done

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread,

and forgive us our trespasses,

as we forgive those who trespass against us,

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

[For thine is the kingdom,

and the power, and the glory,

for ever and ever.]

Amen. - Literal translation:

Our Father being in heaven,

hallow been Thy name.

Thy kingdom come.

Thy will do been in-future

equally on earth and heaven.

Give us our daily bread today,

and forgive us on our not-diligence,

like we forgive our not-diligent(people),

and not-lead us in not-probity

but deliver us from evil.

[Because the kingdom is Thine,

and the power, and the glory,

always-through-future always.]

Amen. - IPA transcription:

[ɾaːs hεdɪs'tan 'dεɾlɑnd εm 'ænːaɾ

'vεɾgɾen dεɾnt 'luhεn nεlt

'luhεn 'kəynɾεl 'dεnˌviεθ̞

'luhεn ɾɪl'neyn gyl dεɾnt gɾanː

'saeʋεɾn sa 'hεɾdɾaɪn an 'ænːaɾ

gan ɾaːm ɾaːs 'daɾsyl mɔnː 'εmdɑɾ

an gaɾ ɾaːm sa ɾaːs hɑːmεɾnɯ'εlɑɾ

'aveɾ ɾaːn gaɾ ɾaːs hɑːmεɾnɯ'ɾanʋɑɾ

an 'hɑːviεθ̞ ɾaːm εm hɑː'ganːan

'lɔɾn 'foɾdaɾn ɾaːm fεɾ gɾɔd

dɾeiɾ en 'kəynɾεl iːɾ 'luhεn

an en dɾeːn an en 'glaðʋin

'vɾaːdgɾayn vɾaːd

'ɑmεn]