KiBantu is a zonal language that is meant to act as a potential lingua franca for the Bantu-speaking peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa. Though it is highly influenced by Swahili, it is slightly simplified and incorporates Bantu vocabulary of disparate origins.

| kiBantu kiBantu | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | |||

| Zonal Auxlang | |||

| Alignment | |||

| Nominative-Accusative | |||

| Head direction | |||

| Head-Initial | |||

| Tonal | |||

| Yes | |||

| Declensions | |||

| No | |||

| Conjugations | |||

| Yes | |||

| Genders | |||

| Yes | |||

| Nouns decline according to... | |||

| Case | Number | ||

| Definiteness | Gender | ||

| Verbs conjugate according to... | |||

| Voice | Mood | ||

| Person | Number | ||

| Tense | Aspect | ||

Phonology[]

KiBantu's phonology is principally derived from that of Proto-Bantu (with the loss of two vowels and the addition of fricatives and glides), although sound correspondences aren't always regular. Like most Bantu languages KiBantu is tonal, though the tones intentionally do not distinguish many minimal pairs.

Vowels[]

KiBantu, like Swahili, Shona, and Zulu, has a simple five vowel system, as opposed to the seven vowel system of some modern Bantu languages and Proto-Bantu. In addition, there is no contrastive vowel length.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e ~ ɛ | o ~ ɔ |

| Open | a ~ ɑ | |

The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ may be realized as close-mid and open-mid, and may be pronounced according to each speaker's preference. There are no diphthongs in KiBantu. All vowel sequences are permitted, and each vowel constitutes a separate syllable. Sequences of two of the same vowels, such as /aa/ or /ee/ are rarely found in word roots, but can often be found in inflected words.

Consonants[]

KiBantu has twenty basic consonant sounds, and an additional thirteen consonants if prenasalized consonants are counted separately.

| Labial | Alveolar | Post-alveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |||

| Stop | voiceless | regular | p | t | c ~ t͡ʃ | k | |

| prenasalized | ᵐp | ⁿt | ᶮt͡ʃ | ᵑk | |||

| voiced | regular | b | d | ɟ ~ d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||

| prenasalized | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᶮd͡ʒ | ᵑɡ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | regular | f | s | ʃ | h | |

| prenasalized | ᶬf | ⁿs | ᶮʃ | ||||

| voiced | regular | v | z | ||||

| prenasalized | ᶬv | ⁿz | |||||

| Approximant | w | l ~ r | j | ||||

- Prenasalised consonants are consonants preceded by a brief homorganic nasal. The homorganic nasal takes on the same place of articulation as the consonant it precedes, though in orthography this is only reflected in the labial consonants, and all other instances of the homorganic nasal are written as ⟨n⟩.

- When modified by the homorganic nasal, the approximants change in predictable ways. /l/ has no prenasalised counterpart, so it becomes /ⁿd/, as seen in nde, an inflected form of -le "long". /w/ similarly becomes /ᵐb/. As an exception, when /j/ undergoes prenasalisation, instead of becoming a prenasalised consonant it becomes the palatal nasal /ɲ/.

- The nasals /m/, /n/, and /ɲ/, as well as /h/, do not change at all when prenasalised.

- The velar nasal [ŋ] does not occur as a separate phoneme, but as a variant of the homorganic nasal before the velar consonants /k/ and /g/.

- The plain palatal stops may either be realized as plosives or affricates. When prenasalized, however, they should be realized as affricates.

- /h/ is rarely found in words of native Bantu origin, and is the only true loan phoneme in KiBantu. Its presence generally, but not always, marks a word as a foreign loan.

- /l/ and /r/ do not contrast in native words and most loanwords, as the phoneme /l/ is almost always used. However, /r/ can occur and is written as such in proper names such as kinyarwanda "Rwanda language".

Tone/Stress[]

KiBantu has two tones, high and low. The high tone has a higher pitch and is indicated with an acute accent, while the low tone is lower and unmarked. The low tone is generally treated as a default, and is generally considered an absence of tone. Unlike in many Bantu languages, tones in KiBantu almost never play any kind of role in distinguishing grammatical features; they simply exist to distinguish similar words. Like in most Bantu languages, only the first syllable of a verb is specified as high or low. All other syllables are usually written as a low tone, but may be realized with whatever tone the speaker desires. Nouns and adjectives are slightly more complicated: tone is only contrasted on the first and last syllable of the stem. This means that for any noun or adjective stem that is longer than two tones, the speaker may realize any of the tones in between the first and final as whatever they desire. There is one exception: in compound nouns, all tones are realized as they are in each of the noun's respective components, even if that violates this principle. Tone does not have to be indicated in more casual writing, as there are not enough minimal pairs to make a text difficult to understand if tone is not written. For example, these roots exemplify a three-way tonal contrast, though they may have different prefixes:

- -kala: to sit

- -kála: charcoal → makála: charcoal

- -kálá: crab → nkálá: crab

There is, however, a small number of nouns or verbs that are solely differentiated by tone:

- izulu "sky" vs. izúlu "nose"

- bwana "master" vs. bwána "childhood"

- -paka "to rub" vs. -páka "to pack"

This article will mark tone when applicable.

Note that stress in KiBantu is independent of tone. In KiBantu, stress always falls on the penultimate syllable.

- mpúku [ˈᵐpú.ku]

- iluba [i.ˈlu.ba]

- kitungulu [ki.tu.ˈᵑgu.lu]

- niungulusa [ni.u.ᵑgu.ˈlu.sa]

- ensayikilopidiya [e.ⁿsa.yi.ki.lo.pi.ˈdi.ya]

Phonotactics[]

The syllable structure in KiBantu is (N)(C)(G)V. The nucleus is always a vowel, and cannot be a syllabic /m/ like in many Bantu languages. Though prenasalized consonants are treated as one consonant phonetically, the homorganic nasal that precedes a consonant can be considered a separate part of the onset. Additionally, one of the glides, /j/ or /w/, may follow most consonants in the onset. Maximal syllable structure can be seen in monosyllabic words such as ngwe /ᵑɡwe/ "leopard" and mbwá /ᵐbwá/ "dog". Final consonants and consonant clusters in foreign loanwords are often broken up using an epenthetic vowel, such as English gram becoming galamu in KiBantu.

Orthography[]

KiBantu is written phonetically with the Latin alphabet. Most letters correspond to one sound, but there are two digraphs discounting prenasalized sounds: ⟨sh⟩, and ⟨ny⟩. These digraphs may often be counted as separate letters. The letters ⟨q⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨x⟩ do not occur in most words, however they can occur in proper names. The English approximations listed below are not meant to indicate the exact pronunciations of the letters, but to serve as a guide for English speakers.

The one orthographic issue that may cause some ambiguity is whether glides should be written between consecutive vowels of differing heights. In word roots, the glides are generally written. The root for mushroom is written -owa, not *-oa, while the root for pear is peya, not *pea. With grammatical extensions, however, the glide is generally not written. For example, the plural of mwáka "year" is written miáka, not miyáka. It is also not written when two vowels are put together in a compound word, such as in kipálaifu "skyscraper," from ki- + -pála + ifu.

Word Formation[]

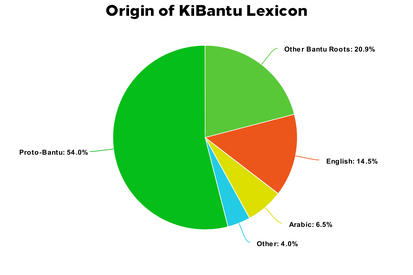

Approximately 74% of KiBantu's lexicon is of native Bantu origin. Of that percentage, 72% is traceable back to a reconstructable Proto-Bantu root, while 28% comes from words of native Bantu origin that are not reconstructable as Proto-Bantu, or words that were derived from other words of Bantu origin. The remaining 26% of KiBantu's lexicon is of foreign origin. Words of English origin make up the bulk of this, at 56% of loanwords, while Arabic contributes 26%. Words from other languages such as Persian, French, Portuguese, and various Indic languages make up the remainder of loanwords in KiBantu.

Derivation from Proto-Bantu[]

In many cases, there are regular or semi-regular correspondences between Proto-Bantu phonemes and KiBantu sounds. Tones, as well, usually correspond exactly to the reconstructed Proto-Bantu root.

| Proto-Bantu Phoneme |

KiBantu correspondence(s) |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| *p | p in most cases, often f before PB /u/ or /i/. | *-pácà > ipása "twin" *-púdò > ifúlo "foam" *-pígò >ifígo "kidney" |

| *t | t in most cases, f before PB /u/, s occasionally before PB /i/. |

*-tɪ́mà > mutíma "heart" *-tù > ifu "cloud" *-pítí > mfísi "hyena" |

| *c | s in most cases, occasionally sh or c. |

*-códì > isózi "tear" *-bɪ́cɪ̀ > -bíshi "raw" *-càca > -caca "to ferment" |

| *k | k in most cases, f before PB /u/, s or sh occasionally before PB /i/. |

*-kɪ́dà > mukíla "tail" *-kútà > mafúta "fat" *-jókì > mushi "smoke" |

| *b | b in most cases, occasionally v before PB /u/, rarely v elsewhere. /w/ when borrowed from Swahili. | *-bààta > ibata "duck" *-búdà > mvúla "rain" *-bába > -váva "to ache" |

| *d | almost always l, d when prenasalized, occasionally z before PB /i/, v before PB /u/. | *-dàdò > kilalo "bridge" *-dèdù > ndevu "beard" *-bʊ́dì > mbúzi "goat" |

| *j | z in many cases, often j as well, rarely y; is often ∅ when it is the first phoneme in a PB root. | *-jʊ̀dʊ̀ > izulu "sky" *-jàdà > njala "hunger" *-jòjá > boyá "fur" |

| *g | g in most cases, occasionally v before PB /u/, rarely z before PB /i/, occasionally ∅ before PB /e/. | *-gòngò > mugongo "back" *-gùbʊ́ > mvubú "hippopotamus" *-gìda > kuzila "to abstain from" *-gènda > kwenda "to go" |

| *m | m in nearly all cases. | *-mààmá > mamá "mother" |

| *n | n in nearly all cases. | *-jínò > ino "tooth" |

| *ɲ | ny in nearly all cases. | *-nyàmà > nyama "animal" |

| *a | a in nearly all cases. | *-jánà > mwána "child" |

| *e | e in nearly all cases. | *-béèdè > ibéle "breast" |

| *ɪ | i in most cases. | *-tɪ́ > mutí "tree" |

| *i | i in most cases, y when followed by another vowel in PB. | *-dɪ̀ndɪ̀ > mulindi "guard" *-dɪ́a > kulya "to eat" |

| *o | o in most cases, rarely u; w when followed by another vowel in PB. | *-bókò > iboko "arm" *-nyóa > kunywa "to drink" |

| *ʊ | u in most cases, rarely o; w when followed by another vowel in PB. | *-jʊ́dʊ̀ > izúlu "nose" *-gʊ̀a > kugwa "to fall" |

| *u | u in nearly all cases. | *-túda > kufúla "to forge" |

Languages Drawn From[]

As Swahili already acts as a lingua franca for East Africa, more of KiBantu's vocabulary was drawn from Swahili than any other Bantu language. However, the vocabulary of KiBantu represents many larger phyla of the Bantu languages. In fact, there is at least one language used as a main reference for vocabulary for each geographic Guthrie zone, totalling 32 languages. These languages usually have over 100,000 speakers, and are among the more prominent Bantu languages spoken today (languages in bold were the ten most major inspirations for KiBantu):

- Zone A: Duala (A24), Bulu (A74)

- Zone B: Bali/East Teke (B75)

- Zone C: Lingala (C32b), Tetela (C71)

- Zone D: Lega-Mwenga (D25)

- Zone E: Kikuyu (E51), Kamba (E55)

- Zone F: Sukuma (F21), Nyamwezi (F22)

- Zone G: Swahili (G42d), Sango (G61)

- Zone H: Kikongo (H16)

- Zone J: Kinyarwanda (JD61), Rundi (JD62), Nyoro (JE11), Nyankore (JE13), Luganda (JE15)

- Zone K: Luvale (K14)

- Zone L: Luba-Kasai (L31)

- Zone M: Bemba (M42), Ila (M63)

- Zone N: Chichewa (N31)

- Zone P: Yao (P21)

- Zone R: Umbundu (R21), Herero (R30)

- Zone S: Shona (S10), Venda (S21), Tswana (S31), Southern Sotho (S33), Xhosa (S41), Zulu (S42)

The following is a list of what percentage of the Bantu roots in KiBantu share a recognizable cognate in the Bantu languages used to provide its vocabulary (to be updated):

- Swahili - 65%

- Chichewa - 63%

- Rwanda-Rundi - 46%

- Shona - 35%

- Xhosa - 33%

- Zulu - 33%

- Luba-Kasai - 32%

- Lingala - 27%

Technological Vocabulary[]

A few words for modern technology are derived from Proto-Bantu. These come through a Bantu language (usually Swahili) in which the word has an older meaning derived from Proto-Bantu and a more modern meaning. In KiBantu, only the modern meaning is kept.

- ndege: airplane (From Swahili ndege, from Proto-Bantu *ndègè "bird")

- muzinga: cannon (From Swahili mzinga, from Proto-Bantu *mʊ̀dɪ̀ngà "beehive")

- mbanzi: missile (From Lingala mbanzi, from Proto-Bantu *mbànjí "arrow")

Grammar[]

KiBantu is an agglutinative language, which means that most words are constructed by joining a root together with many smaller affixes. Its primary word order is SVO, and it is also primarily a head-initial language. Verbs follow the adjective, adjectives follow the noun they modify, and the adpositions in KiBantu are prepositions, not postpositions. Unlike English, there are no articles such as "a" and "the". Another feature common to Bantu languages that KiBantu naturally shares is a variety of noun classes.

Nouns[]

Noun Classes[]

Nouns classes form the core of how KiBantu nouns work. Verbs, adjectives, demonstratives, and some prepositions all inflect to agree with a noun's inherent class. Most noun classes occur in pairs: singular and plural. Numerically and grammatically, the plural is a different class than the singular, though semantically they are the same class. Most classes have an underlying semantic category and patterns of meaning are often identifiable in each class. However, there are many exceptions in almost every class, and noun class is generally arbitrary. Each of the classes has a usual prefix, however, the prefix often changes before a vowel. In all, there are thirteen full noun classes, and three additional secondary noun classes. Note that in the chart below, the classes are numbered with the traditional Bantu numbering system. Like in several Bantu languages, classes 12 and 13 are skipped and are not a class in KiBantu, due to the fact that were present in Proto-Bantu and are still in many extant Bantu languages.

| Noun Class | Prefix before

consonant |

Prefix

before a |

Prefix

before e |

Prefix before i |

Prefix

before o/u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mu- | mw- | mw- | mw- | m- |

| 1a | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ |

| 2 | ba- | b- | ba- | ba- | ba- |

| 3 | mu- | mw- | mw- | mw- | m- |

| 4 | mi- | mi- | mi- | m- | mi- |

| 5 | i- | i- | i- | ∅- | i- |

| 6 | ma- | m- | ma- | ma- | ma- |

| 7 | ki- | c- | c- | k- | c- |

| 8 | bi- | by- | by- | b- | by- |

| 9 | N- | ny- | ny- | ny- | ny- |

| 10 | N- | ny- | ny- | ny- | ny- |

| 9a | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ |

| 10a | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ |

| 11 | lu- | lw- | lw- | lw- | l- |

| 14 | bu- | bw- | bw- | bw- | b- |

| 15 | ku- | kw- | kw- | kw- | k- |

| 16 | pa- | p- | pa- | pa- | pa- |

| 17 | ku- | kw- | kw- | kw- | k- |

| 18 | mu- | mw- | mw- | mw- | m- |

This prefix list may seem daunting, but there are many general rules:

- In most cases, if a class prefix precedes a root starting with the same vowel as the prefix, the prefix becomes the bare consonant. For example, the the root for "child", -ána, which takes class 2 in the plural, becomes bána, not *baána.

- Classes that end in -u become their bare consonants before -o as well as -u. For example, the class 3 root -osí "smoke" is mosí when taking its prefix.

- The class prefixes that end in -i all behave a little differently. The prefix mi- remains mi- before any vowel except i, while ki becomes c- and bi- becomes by- before every vowel except -i.

- Classes 1a, 9a, and 10a do not take any prefix.

Mu-ba class[]

The mu-ba class, known as classes 1 and 2 respectively, is the only noun class in KiBantu that has a totally clear semantic field. Nouns in the mu-ba class refer exclusively to people. Note that this does not mean that all nouns referring to people are within this class, merely that all nouns in this class represent people.

- muntu/bantu: person/people

- mwána/bána: child/children

- mukázi/bakázi: woman/women

- mulúme/balúme: man/men

Agent nouns be derived from verbs and adjectives also regularly appear in the mu-ba class. Agent nouns derived from verbs replace the final -a of the verb with -i.

- kupika: to cook → mupiki/bapiki: chef/chefs

- kulima: to farm → mulimi/balimi: farmer/farmers

- kulóba: to fish → mulóbi/balóbi: fisherman/fishermen

There is also a small subset of nouns of class 1 known as class 1a. Except for classes 9a and 10a, it is the only class without an identifying prefix; nouns in class 1a do not have the mu- prefix in the singular that is characteristic of the mu-ba class. However, nouns in class 1a still take class 2 prefixes in the plural. Most of these words fall into two categories: Bantu kin terms, or borrowed occupations:

- mamá/bamamá: mother/mothers

- tatá/batatá: father/fathers

- ndeko/bandeko: sibling/siblings

- dokotoli/badokotoli: doctor/doctors

- bishopu/babishopu: bishop/bishops

- pápa/bapápa: pope/popes

Mu-mi class[]

The mu-mi class is known as class 3 in the singular and class 4 in the plural. It is one of the most common noun classes, and as such is one of the most semantically varied, though a common thread that can be drawn is that nouns in this class often extend in vertically in one or more directions. Although many potential categorizations will be laid out, there will always be exceptions.

The most stable category is the names of trees. Tree names can be derived systematically by adding the mu- prefix to plants of other classes.

- mutí/mití: tree/trees

- icungwa: orange (fruit) → mucungwa/micungwa: orange tree/orange trees

- ápola: apple → mwápola/miápola: apple tree/apple trees

There are many body parts in the mu-mi class, and they are categorized as extending lengthwise in one direction, or being particularly active.

- mutíma/mitíma: heart/hearts

- mutú/mitú: head/heads

- mukíla/mikíla: tail/tails

- mugulu/migulu: leg/legs

- mufúpa/mifúpa: bone/bones

Tools that extend lengthwise in one direction can also be found in this class.

- mulango/milango: door/doors

- mupanga/mipanga: hatchet/hatchets

- muvwí/mivwí: arrow/arrows

Incorporeal or amorphous things that are considered active also often appear in the mu-mi class.

- mwéya: air

- móto: fire

- mudíma: darkness

- mushí: smoke

- muvuke: steam

- muzímu/mizímu: spirit/spirits

A few flat stretches or expanses can also sometimes be seen in the mu-mi class.

- munda/minda: field/fields

- mukéka/mikéka: mat/mats

- muji/miji: city/cities

Some nouns derived from verbs can also appears in the mu-mi class. These derivations generally replace the final -a of the verb with a final -o. These nouns aren't derived by a regular scheme, and therefore must be memorized.

- kutéga: to set a trap → mutégo/mitégo: trap/traps

- kubánza: to begin → mubánzo/mibánzo: beginning/beginnings.

And finally, a few loanwords that begin with m- have found their way into this class, though they also may fit into some of the aforementioned categorizations.

- munala/minala: tower/towers (from Arabic manāra)

- musumali/misumali: nail/nails (from Arabic mismār)

- munuta/minuta: minute/minutes (from French minut)

- muziki: music (from English music, French musique)

I-ma class[]

Known as classes 5 and 6 respectively, the i-ma class, generally encompasses things that are often found in groups, as well as small round things. But, this is complicated by the fact that this is the class with the second largest amount of loanwords, so assigning a clear semantic field is difficult. In other Bantu languages, such as Swahili and Shona, this class often takes no prefix. However, when these words are loaned into KiBantu, they take the i- prefix.

The i-ma class is prototypically associated with fruits. Though there are some fruits in this class, more words for fruits are in class 9a.

- ibumá/mabumá: fruit/fruits

- icungwa/macungwa: orange/oranges

- igwavá/magwavá: guava/guavas

- ibilingani/mabilingani: eggplant/eggplants

Other small, rounds objects are also occasionally in this class:

- ibwe/mabwe: stone/stones

- igí/magí: egg/eggs

- ikála/makála: piece of charcoal/charcoal

Another common semantic commonality, as mentioned before, is body parts that commonly come in groups or pairs:

- ibóko/mabóko: arm/arms

- ino/mano: tooth/teeth

- ipapu/mapapu: lung/lungs

- iso/maso: eye/eyes

- itú/matú: ear/ears

Other things seen in groups or pairs are also included:

- ifu/mafu: cloud/clouds

- ijáni/majáni: leaf/leaves

- ipása/mapása: twin/twins

There are quite a few words that only occur in class 6 and represent liquids:

- mafúta: fat, grease

- magazí: blood

- maté: saliva

- matope: mud

- mazí: water

A few other words are also exclusively class 6 and have no singular, though there is little that unites these nouns semantically:

- makelele: noise

- malipo: payment

- manéla: ladder

- matálatala: glasses

- mabulugwe: trousers, pants

And finally, there are many loanwords present in this class. Many of these are older loanwords that came into Swahili, and then into other Bantu languages, from Arabic:

- idilisha/madilisha: window/windows (From Arabic drīša)

- idubu/madubu: bear/bears (From Arabic dubb)

- iguniya/maguniya: sack/sacks (From Arabic gūniyya)

- itofali/matofali: brick/bricks (From Arabic tafal)

- isoko/masoko: market/markets (From Arabic sūq)

There are, however a few recent loanwords from English in this class, though more recent loanwords are much more common in class 9a.

- ikándela/makándela: candle/candles (From English candle)

- itawuló/matawuló: towel/towels (From English towel)

- ikéteni/makéteni: curtain/curtains (From English curtain)

Although this is not true in many Bantu languages, in KiBantu the i-ma class tends to be the only class other than class 1 that accepts words for people. These are always loanwords, with the exception of the aforementioned word ipása:

- ishuja/mashuja: hero/heros (From Arabic šujāʿ)

- itilosi/matilosi: sailor/sailors (From Afrikaans matroos)

- ibepali/mabepali: capitalist/capitalists (From Indic language, compare Hindi vyāpārī)

Ki-bi class[]

The ki-bi class is known as class 7 and the singular and class 8 in the plural. It is one of the rarer classes in KiBantu. Its primary semantic field is tools and manufactured objects, however, the majority of nouns in this class do not fall into that category. These words for tools often aren't derived from other words:

- kibiliti/bibiliti: match/matches

- kilatu/bilatu: shoe/shoe

- kinú/binú: mortar/mortars

- kiyiko/biyiko: spoon/spoons

Occasionally words for tools are derived from verbs:

- kukómba: to sweep → kikómbo/bikómbo: broom/brooms

- kukópola: to mop → kikópolo/bikópolo: mop/mops

- kushuza: to filter → kishuzo/bishuzo: filter/filters

- kusana: to comb → kisano/bisano: comb/combs

Despite being the class most prototypically associated with inanimate objects, there are also some animals and plants in this class:

- culá/byulá: frog/frogs

- kikwá/bikwá: yam/yams

- kipepelo/bipepelo: butterfly/butterflies

- kipuká/bipuká: bug/bugs

- kitungulu/bitungulu: onion/onions

There are some abstract nouns in this class as well, both basic and derived:

- kitóko: beauty

- kina: depth

- kwenzwa: to be created → cenzwo: nature

- kusángala: to be happy → kisángalo: happiness

- kuzála: to give birth → kizáli/bizáli: generation/generations

The ki-bi class, however is almost always used as the class for language names, and in fact, is used as such in the name "KiBantu", meaning both "Bantu language" and "language of the people" in KiBantu. Some more language names are as follows:

- Kiswahili: Swahili language

- Kishona: Shona language

- Kixhosa: Xhosa language

- Kizulu: Zulu language

- Kicewá: Chichewa language

- Kingelesi: English language

- Kifaransa: French language

N class[]

Classes 9 and 10 are collectively called the N class, and when 9a and 10a are also counted a little less than 45% of KiBantu nouns are in this class. This is because the singular and plural of this class are the same, so loanwords are incorporated easily. The only way the number of these classes is distinguished is through verbal and genitive concord. Native words most often take a homorganic nasal prefix; this subset of the class contains mostly animal names, and though all the prior mentioned classes except 1 and 2 have some animals within them, classes 9 and 10 contain the majority of animal names.

- nyama: animal/animals

- mbúzi: goat/goats

- mfísi: hyena/hyenas

- mpúku: mouse/mice

- mvubú: hippo/hippos

- ndá: louse/lice

- ngombé: cow/cows

- njíva: dove/doves

- nkálá: crab/crabs

- nsíndí: squirrel/squirrels

- nzovu: elephant/elephants

The rest of the nouns in this class are generally miscellaneous, however, this class too has several nouns derived from verbs. Though these often end in -o like the derived nouns in other classes, this is not always the case.

- kubala: to count → mbala: time, iterations/times, iterations

- kulóta: to dream → ndóto: dream/dreams

- kufema: to breathe → mfemo: breath/breaths

- kufísha: to hide → mfísho: secret

A subset of the N class, called 9a and 10a, is the largest class in KiBantu. It takes all the same concords as regular nouns in the N class, but there is no nasal prefix. About 1/3rd of all KiBantu nouns fall into this subclass. This class consists primary of foreign loanwords, and over 80% of foreign loanwords in KiBantu are placed into this class. This includes loanwords from English:

- keki: cake/cakes (From English cake)

- búku: book/books (From English book)

- hoteli: hotel/hotels (From English hotel)

- ápola: apple/apples (From English apple)

There is also a significant contribution from Arabic, as in the i-ma class:

- sabuni: soap (From Arabic ṣābūn)

- falasi: horse/horses (From Arabic faras)

- zabibu: grape/grapes (From Arabic zabīb)

- dini: religion/religions (From Arabic dīn)

A few Persian loanwords are in this class as well:

- pamba: cotton (From Persian panbe)

- lángi: color/colors (From Persian rang)

- pilipili: pepper/peppers (From Persian pelpel)

- balafu: ice (From Persian barf)

Loans from the Romance languages, primarily Portuguese and French, make up the final significant chunk of loanwords in this class:

- kamyó: truck/trucks (From French camion)

- pasi: clothing iron/clothing irons (From French repasser)

- avoká: avocado/avocados (From French avocat)

- bendela: flag/flags (From Portuguese bandeira)

- mézá: table/tables (From Portuguese mesa)

A few class 9a nouns can be mistaken for nouns of other classes because they seem to have a class prefix when they actually do not. Though these exceptions are relatively few, they must be memorized:

- mita: meter (not class 4)

- injini: engine (not class 5)

- mashini: machine (not class 6)

- matilesi: mattress (not class 6)

- buleki: brake (not class 14)

Lu-N class[]

The lu class is called class 11, however, there is no class 12 to act as its plural. Instead, class 10 acts as the plural for lu class nouns. This class has nearly merged with class 14 in Swahili; however it is still a completely separate class in KiBantu. It is the rarest primary noun class in KiBantu, but as a result it is one of the most semantically coherent. Nearly all nouns in this class are long, relatively flat things. Body parts are among the most salient members of this category:

- lubavu/mbavu: rib/ribs

- lulími/ndími: tongue/tongues

- lunwéle/nwéle: a hair/hair

- lwála/nyála: fingernail/fingernails

Many long, flat objects are in this class as well:

- lukúni/nkúni: piece of firewood/firewood

- lushíngé/nshíngé: needle/needles

- lwembe/nyembe: razor blade/razor blades

- lubawo/mbawo: board/boards

- lupánga/mpánga: sword/swords

Bu class[]

The bu class is class 14. This class is mostly coherent, as it primarily encompasses abstract concepts. As such, most nouns in the class do not have a plural form. A scant few nouns in this class can nevertheless be pluralized in the ma class. The abstract concepts that this class contains are most often derived from nouns, verbs, or adjectives:

- kulima: to farm → bulimo: agriculture

- muntu: human → buntu: humanity

- mwána: child → bwána: childhood

- -cace: few → bucace: scarcity

Country names can also be derived, with some regularity, from the names of languages:

- Kifalansa: French → Bufalansa: France

- Kingelesi: English → Bwingelesi: England

- Kicina: Chinese → Bucina: China

There are a few nouns in the bu class which do not fall into either of these categories, and they also do not have a plural. These nouns are generally lumpy or round in some way, and grammatically they are treated as mass nouns:

- bowa: mushroom

- busó: face

- bongó: brain

- bugali: porridge

There is a final subset of nouns in this class which take ma- in the plural. There is little that unites that semantically, so they must be memorized:

- bushángá/mashángá: bead/beads

- bwáto/máto: boat/boats

- butá/matá: bow/bows

A few loanwords that begin with bu- have also entered from other languages. They are almost always placed in class 14:

- bundúki/mandúki: gun/guns (From Arabic bunduq)

- bulashi/malashi: brush/brushes (From English brush)

- bulanketi/malanketi: blanket/blankets (From English blanket)

Ku Class[]

The ku class, or class 15, is a unique class grammatically. Verbs are fundamentally a bare root in KiBantu, but verbs must take the class 15 prefix when used in isolation or as the compliment of an auxiliary verb. All verbal infinitives are in this class, and they often act just as infinitives or gerunds do in English.

- kulála: to sleep

- kwenda: to go

- kubóna: to see

- kuféma: to breathe

- kuma: to be dry

- kóga: to swim

The Locative Classes[]

The final three noun classes are known as classes 16, 17, and 18, and are not considered primary noun classes like the first thirteen. This is because, in most cases, they are added to a noun in addition to the class prefix it already has. Like other classes, however, the locative classes still take concords and adjectives, verbs, demonstratives and prepositions can agree with them.

The pa locative class:

Known as class 16 numerically, the pa locative represents a definitive location at or on a place or surface. This locative, however, is less used than 17.

- isoko: market → paisoko: at the market

- mugulu: leg → pamugulu: on the leg

- madilisha: windows → pamadilisha: on the window

- ápola: apple → pápola: on the apple

There are a few words that are inherently in this class. They are often derived from other nouns. They can be considered adverbs, but they often act like nouns:

- pakáti: between, among

- pansí: bottom, down

- panze: outside

- pazulu: top, up

- pambele: forward

The ku locative class:

Class 17, the ku locative class, in the most complicated of the three locative classes, but it is also the most commonly used. At its core, it represents a more indefinite or general location. Knowing when to use class 17 rather than class 16 can be difficult, but 17 can generally be used when the speaker is being less specific about where something is.

- kilalo: bridge → kukilalo: on a bridge

- bitenga: roofs → kubitenga: on roofs

It can also be used with certain verbs to contextually mean to or from, rather than at or on.

- kwenda kunyumbá "to go home"

- kwenda kushuli "to go to school"

There are just two words that belong to this class inherently:

- kulyo: right

- kushoto: left

The mu locative class:

The mu locative class, or class 18, expresses interiority. Basically, it shows that that the noun with this prefix is containing another noun within it. The prefix of this class is homophonous with that of both class 1 and class 3.

- sanduku: box → musanduku: in a box

- ndege: airplane → mundege: on an airplane

- nyávu: nets → munyávu: in nets

- munwa: mouth → mumunwa: in the mouth

- izíko: fireplace → mwizíko: in the fireplace

There is only one noun that belongs in this class inherently: mukáti "inside".

Noun Class Derivation[]

Most noun roots in KiBantu are connected with a single meaning. Occasionally, however, several words of distinct meaning can be derived from a single root. The most varied example of this is the root -ntu, which can be used to derive a meaning be on the prototypical meaning of the class

- muntu/bantu: person/people

- kintu/bintu: thing/things

- buntu: humanity

- pantu/kuntu: place

Most derived roots, however, relate more clearly in meaning. The root -tí, which primarily means tree, can be used to derive a few wooden objects:

- mutí/mití: tree/trees

- kití/bití: chair/chairs (thing made from a tree)

- lutí/ntí: stick/sticks (long, extended part of a tree)

Most roots, however, don't have more than one variant:

- kilevu/bilevu: chin/chins

- ndevu: beard/beards

- bitá: war

- butá/matá: bow/bows

Noun Class Concord[]

As stated previously, in KiBantu many words change based on the class of the nouns involved. Though the noun prefix has already been covered, the subject, the prefix of the adjective and the genitive particle -á also change based on the class of the word it agrees with. There are more words that agree with a noun's class, but this is just a general overview.

| Noun Class | Noun Prefix | Adjective | Subject | Object | Genitive (of) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mu- | a- | -mu- | wá | |

| 2 | ba- | bá | |||

| 3 | mu- | u- | wá | ||

| 4 | mi- | i- | yá | ||

| 5 | i- | li- | lá | ||

| 6 | ma- | ya- | yá | ||

| 7 | ki- | cá | |||

| 8 | bi- | byá | |||

| 9 | N- | i- | yá | ||

| 10 | zi- | zá | |||

| 11 | lu- | lwá | |||

| 14 | bu- | bwá | |||

| 15 | ku- | kwá | |||

| 16 | pa- | pá | |||

| 17 | ku- | kwá | |||

| 18 | mu- | mwá | |||

Classes 2, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 are entirely regular, and require little memorization. Class 5 is almost regular, but the subject i- differs from the rest of the concords, which use some variant of li-. Noun classes 3, 4, 6, 9, and 10 (all of which start with nasals) can be considered to have two sets of prefixes: one precedes nouns and adjectives, while the other is used in all other concords. Class 1 is the most irregular class, and the only one outside of the pronominal concords to have a truly divergent form for the subject and the object; the class 1 form of the genitive particle is irregular as well.

In more casual spoken language, only two concords may be distinguished: classes 1 and 2 and whatever they agree with take their normal concords, while anything modified by all other classes (except the locative classes) take the class 9 and 10 concords. Each noun prefix keeps its unique singular and plural, but any verbal subjects and objects, adjectives, or particles act as if they are agreeing with the N class.

Gender/Kinship[]

Though noun class in Bantu languages is often called gender, in KiBantu, like in pretty much all Bantu languages, the noun classes have nothing to do with sex or gender. In fact, there are very few inherently gendered nouns in KiBantu at all. The following are a list of all gendered terms in KiBantu, most of which are kinship terms:

| Male | Female | Neutral |

|---|---|---|

| mulúme "man" | mukázi "woman" | mukúli "adult" |

| tatá "father" | mamá "mother" | muzáli "parent" |

| malúme "maternal uncle" | mama muké/munéni "maternal aunt" |

- |

| tata muké/munéni "paternal uncle" |

shankázi "paternal aunt" | - |

| bwana "gentleman, Mr." | bibi "lady, Mrs." | - |

In terms of kinship, KiBantu does not make many of the distinctions other languages make. However, maternal uncle and paternal aunt are given special terms. Maternal aunts and paternal uncles are formed by combining the words for mother and father with an adjective depending on their age relative to the parent; -ké for younger and -néni for older. Unlike in many Bantu languages, KiBantu does not distinguish cross-cousins from parallel cousins: muzála is the term used for all cousins.

To form all other gendered terms, including those for kinship, careers, and animals, are formed with the special suffixes -kázi and -lúme.

- gogó "grandparent" → gogólúme "grandfather", gogókázi "grandmother"

- mwána "child" → mwánalúme "boy", mwánakázi "girl"

- mutúmiki "waiter/waitress" → mutúmikilúme "waiter", mutúmikikázi "waitress"

- nkókó "chicken" → nkókólúme "rooster", nkókókázi "hen"

- ngombé "bovine" → ngombélúme "bull", ngombékázi "cow"

Note that gender need not be specified in most cases, and is generally only used when absolutely necessary.

Compounding[]

Even compared to English, true compounds are rare in KiBantu. Aside from the gendered compounds mentioned prior, many words that would be expressed by compounds in English may be expressed by genitive constructions in KiBantu.

There, are however, a few true compounds:

- nyezí (reduced form of nyényezí "star") + mukila "tail" → nyezímukila "comet"

- itumba "bud" + bwe "stone" → matumbabwe "coral"

- kímo "state" + ióto "heat" → kímoyóto "temperature"

Compounds may also be derived when phrasal verbs are combined into a new derived noun:

- N- + -púma "to come out" + zúva "sun" → mpúmazúva "east"

- N- + zama "to sink" + zúva "sun" → nzamazúva "west"

- mu- + paka lángi "to paint" (lit. to smear paint) → mupakalángi "painter"

- mu- + píta nzila "to pass by (on the road)" → mupítanzila "passerby"

Pronouns[]

Personal Pronouns[]

Because KiBantu is a pro-drop language, personal pronouns are not seen as often as in English. They are indicated most often through verbal prefixes which almost act like noun class concords, though independent forms exist as well. Like nouns, the independent forms of pronouns do not change based on whether they are the subject or object of the sentence. Nevertheless, the 2nd person singular and 3rd person singular verbal prefixes do have different forms based on whether they are the subject or object. Note that the 3rd person prefixes are represented by the subject and object prefixes of the mu-ba class. The 3rd person prefixes listed on this list, therefore, can only be used for human beings. The pronoun ye can, however, be used for any animate being, but not inanimate ones. On the other hand, the possesive -ake can be used for both animate beings and inanimate objects. The plural -abo, on the contrary, also can only be used for animates; -ake is used to refer to inanimate plurals.

| Pronoun | English | Independent | Subject | Object | Possessive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | I | mi | ni- | -ni- | -angu |

| 2nd singular | you | we | u- | -ku- | -ako |

| 3rd singular | he, she | ye | a- | -mu- | -ake |

| 1st plural | we | ti | tu- | -tu- | -atu |

| 2nd plural | you all | ni | nu- | -nu- | -anu |

| 3rd plural | they | bo | ba- | -ba- | -abo |

| Reflexive | - | - | - | -ji- | - |

Though, as stated above, the independent forms are rare, there are some situations where they are obligatory.

In a situation with a ditransitive verb and three animate actors, the independent forms are used for the direct object.

- bána bangu badinga kulindwa. nikupa bo kwá sasa. "My children need to be watched over. I'm giving them to you for now."

To express the notion of "by __self", one can put the independent form of the pronoun along with -mozi, usually at the end of the clause, as in English:

- nasukula sáhani mi mumozi "I washed the dishes by myself"

- balaenza mukolo monse bo bamozi "they will do all the work themselves"

In addition, mozi has another use with the independent pronouns, and with nouns in general. When used before plural nouns or pronouns with the singular noun prefix, it means "one of ___"

- nitaka kukúmana na mumozi bo "I want to meet one of them"

- sibaziva ete mumozi ni yaandika baluwa "they don't know that one of you wrote the letter"

- nipe kimozi biyiko "give me one of the spoons"

The possessive forms of pronouns are not inflected like adjectives, but instead like the genitive preposition -á. For example, mwána wangu is the correct way to say "my child", rather than *mwána mwangu. In addition, the possesive, when put in a class 17 form, have another use. When used in this way by themselves, it generally conveys the meaning of "to ___", and is placed directly after the verb or at the end of the sentence.

- ili isuwala lá bumoyo na lufo kwabo "it's a matter of life and death to them"

- ibónekana kwangu ete waba wá bwivu "it seems to me that you were jealous"

The reflexive infix is a unique form only seen in a verb's object slot. It refers back to the subject, and is translated as one of the pronouns suffixed with -self in English. For example, nijisukula means "I wash myself" while bajisukula means "they wash themselves".

There are a few verbs whose reflexive meanings differ slightly from their expected meanings, and function as verbs on their own:

- kulila "to cry" → kujilila "to complain"

- kukumisa "to honor" → kujikumisa "to brag"

- kwendesa "to manage" → kujiendesa "to conduct oneself"

There are also a scant few reflexive verbs for which there is no non-reflexive equivalent:

- kujivuna "to be proud"

- kujiganisaganisa "to be concered"

Demonstratives[]

Like in many Bantu languages, KiBantu has three types of demonstratives: a proximal, distal, and remote form. These correspond to the "this", "that", and "yonder" of English. In addition, the distal form is used to discuss something previously mentioned. In general, the proximal form is based on the subject concord of its class. Like in English, these forms can be used as standalone nouns. The distal form is based on the proximal form with an -o replacing its final vowel. Finally, the remote form is the subject concord with the suffix -ya added to the end. Like in many other cases, the class 1 variants of the demonstrative pronouns are slightly irregular.

| Noun Class | Proximal | Distal | Remote |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | uyu | uyo | uya |

| 2 | aba | abo | baya |

| 3 | uwu | uwo | uya |

| 4 | iyi | iyo | iya |

| 5 | ili | ilo | liya |

| 6 | aya | ayo | yaya |

| 7 | iki | ico | kiya |

| 8 | ibi | ibyo | biya |

| 9 | iyi | iyo | iya |

| 10 | izi | izo | ziya |

| 11 | ulu | ulo | luya |

| 14 | ubu | ubo | buya |

| 15 | uku | uko | kuya |

| 16 | apa | apo | paya |

| 17 | uku | uko | kuya |

| 18 | umu | umo | muya |

The distal pronoun also acts as a relative pronoun. Whether it is acting as a subject or an object can be distinguished by using an object marker in the verb:

- mulúme uyo abína "the man who is dancing"

- mukázi uyo nikúnda "the women whom I love"

- mukázi uyo anikúnda "the women who loves me"

- nikúnda kulya mupunga uwo upikwa kwá muvuke "I like to eat steamed rice" (lit. I like to eat rice that is cooked with steam)

Additionally, the class 16 distal pronoun is used to mean "when", even when not agreeing with a class 16 noun. It is usually placed before the verb it modifies:

- apo nalya bugali, nasángala "when I ate porridge, I was happy.

- mpindi mozi apo twakwéla ntaba, twagwa "once when we were climbing up a mountain, we fell.

Interrogatives[]

There are several interrogatives in KiBantu which vary in how they are used. Most behave like adjectives, but a few behave like standalone nouns. The interrogatives are not relative pronouns as they are in English; relative constructions are accomplished through different means.

The interrogative -pi translates to "which", "what", or "what kind of" in English. Unlike the demonstratives, it is declined as a regular adjective. Though -pi can not usually act as a standalone noun, when combined with the locative prefixes to create papi, kupi, and mupi, it can be used as "where".

The words náni and kiyi mean "who" and "what" respectively. Similar to English, náni is used for human agents while kiyi is used for things.

Another interrogative that acts as an adjective is -ngapi, which means "how many" or "how much" when used with a mass noun. It also acts as a regular adjective.

The adverbial question word lini is used to mean "when". Unlike in English, lini always comes at the end of a sentence.

The interrogatives can all be seen in the following list:

| Asking about? | English | KiBantu |

|---|---|---|

| specification | which | -pi |

| location | where | papi, kupi, mupi |

| amount | how many | -ngapi |

| person | who, whom | náni |

| thing | what | kiyi |

| time | when | lini |

Adjectives[]

Like in most Bantu languages, there are few true adjectives in KiBantu, with about twenty in total if the numerals are not counted. Most concepts that would be expressed with adjectives in English are expressed with verbs or genitive constructions in KiBantu. All true adjectives in KiBantu are of native Bantu origin. They are also a closed class, although a few adjectives are idiosyncratically derived from verbs (-kúlu and -kúle from -kúla, -ílu from -íla). As seen previously, most adjectives inflect based on noun class. However, the numeral kúmi "ten" is the only invariable adjective. Generally, adjectives in KiBantu refer to size, state, quantity, value, color or reference.

| Size | State | Quantity | Value | Color | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -fúpi: short | -bíshi: unripe, raw | -cace: few | -bí: bad | -kúndu: red | -inye: other, another |

| -ké: small, little | -dála: old | -íngí: many, a lot | -izá: good | -yélu: white, bright | -pi: which |

| -kúle: far, distant | -shá: new, young | -ngapi: how many | -kúlu: great, main | -ílu: black, dark | |

| -le: long, tall | -túpu: empty | -onse: all, every | |||

| -néne: big, large | |||||

Numerals[]

Basic Numerals[]

The numbers 1-10 are treated as adjectives in KiBantu. For the numbers 1-10, the independent names of the numerals used in counting are the same as their adjective counterparts:

- -mozi: one

- -bilí: two

- -tátu: three

- -ne: four

- -táno: five

- -tándatu: six

- -sambo: seven

- -náne: eight

- -kenda: nine

- kumi: ten

Compound numerals in which the two numbers are being added are written using na between them. In these cases, all numbers in the compound still inflect for noun class. Therefore, kumi na -mozi means "eleven", kumi na -bilí means "twelve", etc.

In compound numerals where the two numbers are being multiplied, the smaller number follows the larger one and they are written as one word. So kumibilí means "twenty", kumitátu means "thirty", etc. These numbers do not inflect for noun class.

Note that the plural form of the numeral -mozi can mean "some", both with countable and mass nouns:

- miji mimozi "some cities"

- mazí mamozi "some water"

- mushanga mumozi "some sand"

Higher Numerals[]

Unlike the numbers 1–99, the higher numbers in KiBantu are nouns:

- izana: hundred

- nkóto: thousand

- imiliyoini: million

To act as numerals, they must be paired with one of the basic numerals. After that, they can be used as numerals normally, except that they do not take any class prefixes. :

- kuba na mémé izana limozi na nkenda kumunda "there are a hundred and nine sheep in the field"

- Bufúmu Bukúlu bwá Roma bwabyála kwá miáka nkóto mozi "the Roman Empire reigned for a thousand years"

- mamiliyoni kumi yá bantu munyika mwatu yadinga kulya "tens of millions of people in our country need to eat"

Ordinal Numerals[]

To form ordinal numbers, simply make -á precede the bare numeral. For example, -á mozi means "first", -á bilí means "second", -á kumi means "tenth", and -á kumibilí na táno means "twenty fifth".

Fractions[]

Forming fractions is somewhat more complicated than in English. If 1 is in the numerator, the word kigabo "part" is used followed by an ordinal. So kigabo cá bili is "one half", kigabo cá tátu is "one third", kigabo cá ne means "one fourth", etc. When the number in the numerator is not 1, the numerator is used following the preposition kwá and the normal number is used with bigabo. For example, bigabo bitátu kwá bilí is "two thirds", bigabo bine kwá tátu is "three fourths".

Word Order[]

There is one thing that distinguishes numerals from normal adjectives: word order. The word order for noun modifiers is as follows: possessive pronoun, adjective, demonstrative, then numeral.

- mbwá zake nyélu nsambo "his seven white dogs"

- bána batu baké baya bane "those four small children of ours"

- inanasi langu libíshi ilo limozi "that one unripe pineapple of mine"

Verbs[]

Verbs are the most complex part of KiBantu. In addition, verbs are usually the core of a sentence, containing much of the relevant grammatical information. As mentioned before, infinitive verbs are class 15 nouns which start with ku-. Verbal roots almost always end in -a, though there are two exceptions. The infinitive of the verb "to be" is kuba, but the form -li is used in the present indicative tense. Additionally, the verb kuti "to say" ends in -i. Unlike Swahili, foreign verbs are fully assimilated and end in -a, though foreign verbs are rare in the first place. Though a few concepts are expressed through changes in the final vowel, most grammatical information is conveyed by using prefixes.

Subject/Object Prefixes[]

Note that the subject and object prefixes do not directly follow each other when there is a tense prefix; the tense prefix comes between the subject and the object. Note that the object prefix is never required, and generally isn't used when their is an object external to the verb. There are negative forms of the subject prefixes, which are regularly formed by having ka- precede the prefix. Note that the simple si- prefix can stand for the negative first person singular, though using the regular form is not incorrect. In addition, the class 1 singular is slightly irregular: it uses the bare ka- prefix, rather than the expected kaa-. In the negative present tense, an -i also replaces the usual root final -a. A table below with the verb kukáta "to cut" is shown. a- is used as the subject for the object slot.

| Noun Class | Subject | Object | Negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | nikáta | anikáta | sikáti

kanikáti |

| 2nd singular | ukáta | akukáta | kaukáti |

| 1st plural | tukáta | atukáta | katukáti |

| 2nd plural | nukáta | anukáta | kanukáti |

| 1 | akáta | amukáta | kakáti |

| 2 | bakáta | abakáta | kabakáti |

| 3 | ukáta | aukáta | kaukáti |

| 4 | ikáta | aikáta | kaikáti |

| 5 | likáta | alikáta | kalikáti |

| 6 | yakáta | ayakáta | kayakáti |

| 7 | kikáta | akikáta | kakikáti |

| 8 | bikáta | abikáta | kabikáti |

| 9 | ikáta | aikáta | kaikáti |

| 10 | zikáta | azikáta | kazikáti |

| 11 | lukáta | alukáta | kalukáti |

| 14 | bukáta | abukáta | kabukáti |

| 15 | kukáta | akukáta | kakukáti |

| 16 | pakáta | apakáta | kapakáti |

| 17 | kukáta | akukáta | kakukáti |

| 18 | mukáta | amukáta | kamukáti |

When the noun class of a subject or object is unknown or cannot be specified, the mu-ba class is used for humans, the mu-mi class is used for plants, the ki-bi class is the generic class for non-living objects, and the N class is used for animals.

There is also a special construction that often uses object prefixes; when parts of the body are being talked about, the affected entity is generally given an object prefix, rather than the possesive that might be used in English:

- ajisukula mabóko "she washed her (own) hands"

- amusukula mabóko "she washed her (someone else's) hands"

- twayikáta mutú ngulube "we cut the pig's head off"

- sitaki kukubóna busó tena kamwe "I never want to see your face again"

Indirect Objects[]

As in English, when there is an indirect object, it is generally placed closest to the verb, paralleling where the object marker is:

- nipa mbwá mfúpa "I give the dog a bone" vs. niyipa mfúpa "I give it a bone"

- abónesa mukázi mbwá "he shows the woman the dog" vs. amubónesa mbwá "he shows her the dog"

- upósita gogókázi baluwa "you mail grandmother a letter" vs. umupósita baluwa "you mail her a letter"

In sentences where both the indirect object and direct objects are pronouns, the independent form (or a demonstrative, for inanimates) is used for the direct object; two object markers are not permitted:

- nimubónesa we "I show you to her"

- nikupa ye "I'll give it (e.g. a dog) to you"

- umupósita iya "you mail that to her"

When the direct object is a pronoun but the indirect object is not, both must be independent forms, and no object marker is used:

- nibónesa mukázi we "I show you to the woman"

- upósita gogókázi iyo "You mail this to your grandmother"

- apa mwána wake ye "he gives it (e.g. a dog) to his child"

Tense[]

After the subject prefix, which has already been discussed, the tense prefix follows. The simple present tense has no prefix. Unlike in many Bantu languages, there are only three basic tenses: past, present, and future.

The past tense is formed somewhat irregularly, but all the tenses involve the tense infix -a-. In most cases, they have the same form as the genitive particle, except that the class 1 prefix has an irregular form. In this tense, -i is not used as a final vowel in negative forms like in the present.

| Noun Class | Subject Prefix | Past Form |

|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | ni- | na- |

| 2nd singular | u- | wa- |

| 1st plural | tu- | twa- |

| 2nd plural | nu- | nwa- |

| 1 | a- | ya- |

| 2 | ba- | baa- |

| 3 | u- | wa- |

| 4 | i- | ya- |

| 5 | li- | la- |

| 6 | ya- | yaa- |

| 7 | ki- | ca- |

| 8 | bi- | bya- |

| 9 | i- | ya- |

| 10 | zi- | za- |

| 11 | lu- | lwa- |

| 14 | bu- | bwa- |

| 15 | ku- | kwa- |

| 16 | pa- | paa- |

| 17 | ku- | kwa- |

| 18 | mu- | mwa- |

- abóna "he/she sees" → yabóna "he/she saw"

- nikibaka "I build it → nakibaka "I built it"

- kaukímbi "you don't wander" → kawakímba "you didn't wander"

There is another small irregularity. For verbs that begin with a, their past tense is the same as their present in classes 2, 6, and 16:

- baandika "they write"/"they wrote"

- yaalukana "they differ"/"they differed"

- paanzama "they float/they floated"

The future tense is formed by using -la-.

- abóna "he sees" → alabóna "he will see"

- nikibaka "I build it → nilakibaka "I will build it"

- kaukímbi "you don't run" → kaulakímba "you will not run"

Mood[]

There are three major moods in KiBantu: the indicative, subjunctive, and imperative. The indicative has already been covered, and is used in most statements.

Imperative[]

The imperative mood is used solely for direct commands and only has a present tense. When addressed towards one person, the imperative is simply the bare verb stem ending in -a. The imperative does not take a subject. When there is an object, including the reflexive prefix ji-, the final suffix becomes -e.

- kala! "sit down!"

- bína! "dance!"

- jifishe "hide!" (lit. "hide yourself")

- ménye macungwa! "peel the oranges!"

For verbs that are one syllabe, the ku- infinitive remains.

- kuza apa! "come here!"

- kulye macungwa! "eat the oranges!

When giving an order to multiple people -ni is added as a suffix.

- kala → kalani "(you all) sit down!"

- jifishe → jifisheni "(you all) hide!"

- ménye macungwa! → ményeni macungwa! "(you all) peel the oranges!"

There is no negative imperative. The negative subjunctive generally fills that role.

Subjunctive[]

The subjunctive mood is used in many more cases than the imperative. The regular subjuctive is created by placing an -e vowel at the end of the verbal root. The negative subjuctice uses -si- for the negative, but places it between the subject and the object rather than at the front of the verb like -ka-. The subjunctive has four primary purposes.

- Used to form negative commands:

- usife! "don't die!"

- nusilye macungwa! "(you all) don't eat the oranges!"

- usijifishe "don't hide!"

- Also used to form additional commands in the same sentence as one imperative command. Two or more imperative commands do not occur in the same sentence:

- enda kukisímá na utéke maji "go to the well and fetch some water"

- wakisa televisheni, ukale, mpí uyitále "turn on the TV, sit down, and watch it"

- Used to advise or in a hortative way:

- tuende kupaki! "let's go to the park!"

- ulye mboga zako "you should eat your vegetables"

- bantu bakúndane "people should love each other"

- And finally, the subjunctive is used after certain conjunctions or verbs that express obligation or necessity.

- nisoma ili nifúnde "I read so that I learn"

- yataka musukule mavali yanu "she wanted you to wash your clothes"

In general, the subjunctive must be used after the following verbs:

- kudinga "to need"

- kulikya "to hope"

- kusénga "to ask, demand"

- kutaka "to want"

Derivations[]

Verbal derivations consist of several endings that can modify the meaning of the base verb. Unlike in other areas of KiBantu, the verbal extensions all have a vestige of vowel harmony. This usually manifests in the each suffix having two forms, which are chosen according to the vowel that directly precedes it: one which that after the vowels -a, -i, and -u, and one that follows -e and -o. Suffixes that begin with a-, however, only have one form.

Applicative: -ela/ila[]

The applicative is the suffix that can produce the widest variety of meanings of all the KiBantu derivational suffixes. It is sometimes called the "prepositional" suffix, as these verbs often translate to a verb and a preposition (most often "to" or "for") in English. Many applicative verbs can take both a direct and indiect object. However, many applicative verbs can have just one object.

- kulila: to cry, weep → kulilila: to mourn, weep for

- kuléta: to bring → kulétela: to bring to

- kuvota: to vote → kuvotela: to vote for

Causitive: -esa/isa[]

The causitive is used to make intransitive verbs, or rarely adjectives, transitive. It can also sometimes be used on other transitive verbs.

- kufúnda: to learn → kufúndisa: to teach

- kugwa: to fall → kugwisa: to drop

- kuseka: to laugh → kusekesa: to make laugh

Note that there are multiple irregular forms of the causative suffix when applied to verbs that already have an existing suffix. For verbs whose stem is more than two syllables that end in -ila or -ela, that suffix is replaced with -isa/-esa, depending on the vowel:

- kutelela: to be slip → kutelesa: to make slip

- kusinzila: to be sleepy → kusinzisa: to make sleepy

Conversive: -ola/ula[]

The conversive forms a verb that means the opposite of what its original form. Like in many Bantu languages, this suffix no longer produces new words, and is only used in a few pre-established words:

- kufisha: to hide → kufishula: to reveal, expose

- kufúnga: to open → kufúngula: to close

- kuvala: to put on (clothes) → kuvula: to undress

- kuziba: to block → kuzibula: to unblock

Passive: -wa/ewa/iwa[]

The suffix -wa is a passive suffix which is applied directly to the root of a verb without the final -a. Verbs whose bare roots end in -wa or -ya (but not -nya) take -ewa or -iwa instead, depending on vowel harmony rules.

- kubóna: to see → kubónwa: to be seen

- kubaka: to build → kubakwa: to be built

- kulya: to eat → kulyiwa: to be eaten

- kusíya: to abandon → kusíyiwa: to be abandoned

An agent can be stated by using the preposition na following the passive verb, much like the "by" of English.

nibóna mbwá: I see the dog → mbwá ibónwa na mi: the dog is seen by me

ulya bilyo: you are eating food → bilyo bilyiwa na we: the food is eaten by you

Mediopassive: -eka/ika[]

This derivational stem is also often called the stative. At its most basic level, it makes transitive verbs intransitive. It basically acts like the passive without implying an agent.

- kubóna: to see → kubóneka: to appear

- kubúla: to break (something) → kubúlika: to break, to be broken

This extension can also be used to express capability or potential of being done, often translated using the "-able" suffix of English.

- kusoma: to read → kusomeka: to be readable, legible

- kulya: to eat → kulyika: to be edible

Often, a single verb can have both of these meanings. For example, kubúlika can either mean "to break" or "to be breakable" depending on the context.

There is a special form of the mediopassive used with verbs that end in the suffixes -ula or -ola: -uka and -oka, depending on the vowel.

- kusongola: to sharpen → kusongoka: to be sharpened

Unlike the passive suffix, the preposition na cannot be used to imply an agent.

Reciprocal: -ana[]

The reciprocal adds the meaning of "each other" to the verb:

- kubóna: to see → kubónana: to see each other

- kufúndisa: to teach → kufúndisana: to teach each other

- kuziva: to know → kuzivana: to know each other

Note that a few verbs might appear to have one of these suffixes, but there may be no corresponding verb that it is derived from. This most often occurs with suffixes that seem to resemble either the applicative or conversive:

- -telela: to slip, not derived from *-tela

- -bóngola: to translate, not derived from *-bónga

- -fúnika: to cover, not derived from *-fúna

There are also a few verbs that are clearly related to other verbs, but take an otherwise non-existant suffix. This is used in KiBantu to slightly aid memory:

- kushanga: to be surprised → kushangaza: to announce

- kubóna: to see → kubónya: to warn

Prepositions[]

Like true adjectives, prepositions are rare in KiBantu. There are only three true prepositions, and two of which have been mentioned previously: -á and na, and one of which is more obscure: nga.

-á can be used with certain nouns to create constructions that are similar to English adjectives:

- ajabu: wonder → -á ajabu: wonderous, amazing

- nguvu: strength → -á nguvu: strong

- mbilo: speed → -á mbilo: fast

- basáli: inhabitants → -á basáli: inhabited

-á has several additional uses in is class 17 form, kwá. It can be used to mean "from" or "out of".

- mulúme kwá Tanzaniya "a man from Tanzania"

- nagula mabumá kwá muwebi "I bought fruit from a merchant"

kwá can also having the meaning of "using" or "by means of"

- yakifúla kwá nyundo yá nsímbi "he forged it using an iron hammer"

- nilashinda timu nyinye kwá bongó "I will beat the other team using intelligence"

And finally, kwá can also express duration in expressions of time:

- twakóla kwá síku ntátu "we worked for three days"

- baalwa kwá miáka "they fought for years"

The other preposition, na, does not inflect. Its most common meaning is "with" or "and."

It can be used to link two nouns, adjectives, verbs. It can also connect two clauses, acting as a conjunction:

- mamá na tatá balaláka "mother and father will be angry"

- mwelé uli mukáli na mushá "the knife is sharp and new"

- mbala nyingi balya na banwa "they often eat and drink"

- ndabónesa bo mucolo wangu, na ndababúnza kana bausángalila "I showed them my drawing, and I asked whether they enjoyed it"

When used following kuba, there are two meanings expressed with na. When there is a subject, it expresses ownership and is translated as "to have."

- nili na macungwa matáno "I have five oranges"

- waba na nyúmba yá kitóko "you had a beautiful house"

- noki, Yohane alaba na mótoka nshá "soon, John will have a new car"

When there is not a subject and kuba na begins a sentence, it has an existential meaning, usually translated as "there is/are":

- kuba na ngombe paya "there is a cow over there"

- kuba na muntu mwinye munyumbá "there is someone else inside the house"

And finally, when used following a passive verb, it is equivalent to "by" in English.

- bilyo bilyiwa na bafúndi "the food was eaten by the students"

In addition, some verbal infinitives can be used in ways that resemble prepositions:

- niweza kwimba leta zose kusóka A kwenda Z "I can sing every letter from A to Z" (lit. I can sing every letter coming from A going to Z)

All other words that are typically prepositions in English are translated by using what are called complex prepositions. These prepositions combine adverbs or nouns with -á in order to make words that function as prepositions. This is usually done with words that describe location:

- nyumá: back, rear → nyumá yá: behind, after

- mbele: front → mbele yá: in front of, before

- panze: outside → panze pá: outside of

- pantu: place → pantu pá: instead of

Adverbs[]

Firstly, there are a few words in KiBantu that are adverbs by default. Like adjectives, this is a closed class, and they are relatively few. These are usually borrowed from Swahili, and they are invariable.

- sana: very

- tena: again

- sasa: now

- muno: too (much)

There are also a few words that can act as adverbs, as well as nouns. These tend to refer either to time or location:

- lelo: today

- zulo: yesterday

- kulyo: right

- pakáti: inside

True adjectives can act like adverbs as well. Unlike in Swahili, the bare form of the adjective is used. They are also used following the verb:

- tuenza iza "we are doing well"

- wapika bí sana nyama "you cooked the meat very badly"

- udinge kujilegesa cace "you need to relax a bit"

- basoma ingi búku "they read a lot"

Analogous to the genitive adjectives are the prepositional adverbs. They are formed just like the genitive adjectives, but always use the class 17 kwá form.

- mbilo: speed → kwá mbilo: quickly

- bulikyo: hope → kwá bulikyo: hopefully

Conditionals[]

Conditionals in KiBantu are formed by using the conjunction: kana, meaning "if". The verb is generally put into the subjunctice mood:

- kana uténge bilyo, uweze kulya "if you bought food, you would be able to eat"

- kana banikólele, nibalipe malí maingi "if they worked for me, I would pay them a lot of money"

The word kana can also be used to mean "whether" in indirect questions:

- ndabúnza kana yacelwa "I asked whether he was late."

Comparison[]

KiBantu does not have a comparative particle like in English.

For comparisons, the verb kupíta "to surpass" is most often used.

- cayi kili ciza kupíta káwa "tea is better than coffee"

- nili na káwa kumupíta "I have more coffee than her" (lit. I surpass her (in) having coffee)

In many cases, nouns are also used where adjectives would be used in English. In such cases, comparisons using kwá can be used.

- nikupíta kwá bulembu "I am weaker than you" (lit. I surpass you in weakness)

- apíta bakázi baonse kwá kitóko "she is the most beautiful (lit. she surprasses all woman in beauty)

When one wants to indicate a superlative meaning sana "very" can also be used as a shorthand:

- ukúnda sana lángi mpi? "What's your favorite color" (lit. Which color do you like a lot?)

Vocabulary[]

Country and Language Names[]

In general, there are two types of country names in KiBantu: those derived from ethnicities and those not.

For those derived from ethnicities, bu- is used to derive the country, mu- the person, and ki- the language, for example

-rundi → Burundi, Murundi, Kirundi (Burundi, Burudian, Rundi)

-fini → Bufini, Mufini, Kifini (Finland, Finn, Finnish)

Most countries not derived from an ethnicity are class 9a, and generally do not have a language associated:

Tanzaniya → Mutanzaniya (Tanzania → Tanzanian)

Note that the language names of some African countries are irregular.

Word List[]

For a full dictionary, see: here.[]

Basic Phrases[]

| English | KiBantu |

|---|---|

| Welcome | Kalibu |

| Hello | |

| What's your name? | Izína lako lili kiyi? |

| My name is... | Izína langu li... |

| Where are you from? | Usóka kupi? |

| I am from... | Ndisóka ku... |

| Pleased to meet you | Ukúndiswa kukubóna |

| Bon appetit | Sángalile(ni) bilyo |

| Bon voyage | Lwendo lwiza |

| Do you understand? | Ueleyela? |

| I understand | Ndieleyela |

| I don't understand | Sieleyeli |

| I don't know | Simanyi |

| Do you speak...? | Uvúga...? |

| How much is it? | Muténgo wake uli mungapi? |

| Sorry | Póle |

| Where's the bathroom? | Wece ili kupi? |

| I love you | Nikukúnda |

| Help! | Sandisa! |

| Call the police! | Íte polísi! |

| Merry Christmas | Kisimasi kiza |

| Happy New Year | Mwáka mushá mwiza |

| Happy Birthday | Síku yá kuzálwa nyiza |

| My hovercraft is full of eels | Gali yá kwanzama langu ijála na mikúngá |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 1)[]

| English | KiBantu |

|---|---|

| All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Bantu baonse bazálwa bá nkulúliko, balingana kwá lokúmú na

malungilo. Bajáliswa kwá akili na zamili, mpí bapaswa kwenzelana muntu na mwinye kwá bundeko. |

Swadesh List[]

| No. | English | KiBantu |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | mi |

| 2 | you (singular) | we |

| 3 | he | ye |

| 4 | we | ti |

| 5 | you (plural) | ni |

| 6 | they | bo |

| 7 | this | uyu |

| 8 | that | uyo |

| 9 | here | apa, uku, umu |

| 10 | there | apo, uko, umo |

| 11 | who | ndáni |

| 12 | what | kiyi |

| 13 | where | papi, kupi, mupi |

| 14 | when | lini |

| 15 | how | nganí |

| 16 | not | ka-, -si- |

| 17 | all | -ónse |

| 18 | many | -íngí |

| 19 | some | -mozi |

| 20 | few | -cace |

| 21 | other | -inye |

| 22 | one | -mozi |

| 23 | two | -bilí |

| 24 | three | -tátu |

| 25 | four | -ne |

| 26 | five | -táno |

| 27 | big | -néni |

| 28 | long | -lé |

| 29 | wide | |

| 30 | thick | |

| 31 | heavy | -zito |

| 32 | small | -ncí |

| 33 | short | -fúpi |

| 34 | narrow | -á muké |

| 35 | thin | -ónda |

| 36 | woman | mukázi |

| 37 | man (adult male) | mulúme |

| 38 | man (human being) | muntu |

| 39 | child | mwána |

| 40 | wife | mukázi |

| 41 | husband | mulúme |

| 42 | mother | mama |

| 43 | father | tata |

| 44 | animal | nyama |

| 45 | fish | mbisi |

| 46 | bird | nyoni |

| 47 | dog | mbwá |

| 48 | louse | ndá |

| 49 | snake | nyóka |

| 50 | worm | munyo |

| 51 | tree | mutí |

| 52 | forest | mwítú |

| 53 | stick | lutí |

| 54 | fruit | itunda |

| 55 | seed | mbégu |

| 56 | leaf | ijáni |

| 57 | root | muzi |

| 58 | bark | igánda |

| 59 | flower | iluwa |

| 60 | grass | byasí |

| 61 | rope | mukozí |

| 62 | skin | igánda |

| 63 | meat | nyama |

| 64 | blood | magazí |

| 65 | bone | mufúpa |

| 66 | fat | mafúta |

| 67 | egg | ikí |

| 68 | horn | pembe |

| 69 | tail | mukila |

| 70 | feather | lunsálá |

| 71 | hair | nwéle |

| 72 | head | mutú |

| 73 | ear | itwi |

| 74 | eye | iso |

| 75 | nose | izúlu |

| 76 | mouth | mulomo |

| 77 | tooth | ino |

| 78 | tongue | lulími |

| 79 | fingernail | lwála |

| 80 | foot | mugulu |

| 81 | leg | mugulu |

| 82 | knee | iví |

| 83 | hand | ibóko |

| 84 | wing | ibabá |

| 85 | belly | itumbo |

| 86 | guts | matumbo |

| 87 | neck | nshíngó |

| 88 | back | mugongo |

| 89 | breast | ibéle |

| 90 | heart | mutíma |

| 91 | liver | kibíndi |

| 92 | drink | -nywa |

| 93 | eat | -lya |

| 94 | bite | -lúma |

| 95 | suck | -munya |

| 96 | spit | -cíla maté |

| 97 | vomit | -sanza |

| 98 | blow | -pépa |

| 99 | breathe | -fema |

| 100 | laugh | -seka |

| 101 | see | -bóna |

| 102 | hear | -umva |

| 103 | know | -manya |

| 104 | think | -wánza |

| 105 | smell | -nusa |

| 106 | fear | -óba |

| 107 | sleep | -lála |

| 108 | live | -ba na bumoyi |

| 109 | die | -fa |

| 110 | kill | -fisa |

| 111 | fight | -lwa |

| 112 | hunt | -saka |

| 113 | hit | -béta |

| 114 | cut | -káta |

| 115 | split | -pasula |

| 116 | stab | -dunga |

| 117 | scratch | -kwenya |

| 118 | dig | -cimba |

| 119 | swim | -ógela |

| 120 | fly | -uluka |

| 121 | walk | -enda |

| 122 | come | -fika |

| 123 | lie | -lála |

| 124 | sit | -kala |

| 125 | stand | -ma |

| 126 | turn | -jika |

| 127 | fall | -gwa |

| 128 | give | -pa |

| 129 | hold | -páta |

| 130 | squeeze | -kámula |

| 131 | rub | -cuba |

| 132 | wash | -osha |

| 133 | wipe | -fúta |

| 134 | pull | -vuta |

| 135 | push | -súkuma |

| 136 | throw | -ponsa |

| 137 | tie | -fúndika |

| 138 | sew | -sona |

| 139 | count | -bala |

| 140 | say | -ti |

| 141 | sing | -imba |

| 142 | play | -kína |

| 143 | float | -anzama |

| 144 | flow | -yela |

| 145 | freeze | -ganda |

| 146 | swell | -vímba |

| 147 | sun | izúva |

| 148 | moon | mwézi |

| 149 | star | nyényezí |

| 150 | water | maji |

| 151 | rain | mvúla |

| 152 | river | lwizi |

| 153 | lake | iziba |

| 154 | sea | nyanzá |

| 155 | salt | munyu |

| 156 | stone | ibwe |

| 157 | sand | mucanga |

| 158 | dust | vumbí |

| 159 | earth | nsi |

| 160 | cloud | ifu |

| 161 | fog | nkungú |

| 162 | sky | izulu |

| 163 | wind | mupépo |

| 164 | snow | teluji |

| 165 | ice | balafu |

| 166 | smoke | mosí |

| 167 | fire | móto |

| 168 | ash | ivú |

| 169 | burn | -sha |

| 170 | road | nzila |

| 171 | mountain | ntaba |

| 172 | red | -kúndu |

| 173 | green | -á kijáni |

| 174 | yellow | -á njano |

| 175 | white | -yéla |

| 176 | black | -indu |

| 177 | night | busíku |

| 178 | day | síku |

| 179 | year | mwáka |

| 180 | warm | -á ióto |

| 181 | cold | -á malíli |

| 182 | full | -jála |

| 183 | new | -shá |

| 184 | old | -dála |

| 185 | good | -iza |

| 186 | bad | -bí |

| 187 | rotten | -boli |

| 188 | dirty | -dugula |

| 189 | straight | -noka |

| 190 | round | -vúlunga |

| 191 | sharp | -káli |

| 192 | dull | |

| 193 | smooth | -á busalali |

| 194 | wet | -á maji |

| 195 | dry | -uma |

| 196 | correct | -lungila |

| 197 | near | -ba pafúpi |

| 198 | far | -kúle |

| 199 | right | kulyo |

| 200 | left | kushoto |

| 201 | at | pa-, ku- |

| 202 | in | mu- |

| 203 | with | na |

| 204 | and | na |

| 205 | if | kana |

| 206 | because | kwá kuba |

| 207 | name | izína |