Setting[]

Vöxek is a constructed language that began to be built in 2006. It's the base for Vöchsers, the first language that came from Old Vöxek basis. The objective of Vöxek is to be a language base for North Germanic conlangs that may be created in the following years. Vöxek consists in a linguistic attempt to reunite common European languages' features to create friendly North Germanic languages. Old Vöxek (gen.term) should be easy for whom speaks one or more North Germanic languages, preferably one or more Southern (DE, NL, etc) and one or more Northern (DK, NO etc), and fluent in English. Vöchsers requires, besides these, proficiency in one or two romance languages and notions of Celtic script.

Origins[]

What/took from which language?

What influence Vöxek received from other languages, languages which were used as basis, or maybe or at least for comparisons; division of the language in phases accordingly and during to its development.

{C}Vöxek is a Germanic/Scandinavian language, an entirely new classification which I had the pleasure to implement. Thus, it is more likely that you find vocabularies/structures in Vöxek connected with this category. Of course, it is a very wide form of classification, which opens gates to uncountable interpretations about how it has been made and how it has been set. When I say it's a Germanic/Scandinavian language I want to say that the majority of the influences came from that root, though it's only general. The synthesis made below does not mean that in any way, all words belonging to the class mentioned were fully copied from the real language, but that a few words of this class were influenced by the system of that language, in the formation/creation of the new word in Vöxek.

Influenced? Yes!

Do you know why do the Scottish people pronounce the word "fight" as "feicht", or "dead" as "deed" or they do not say "gone", but "geed"? Why do the Irish people say: "Do you have money on ye" instead of "Have you got money?" (GB) or "Do you have some money?" (US)? Why do the same Irish make a distinction between the forms of the pronoun "you" in the plural form as "youse" if every speaker know that "you" for singular and for plural are the same thing in English? And what about the typical Irish word: "fecking"? Why do the Australian say "lyk" for "lake" and "tyk" for "take"? Why do the British say "betttta", while Americans would surely correct: "beddur"? An Irish would say "betshurr", while the same would ask a Scottish guy: "What, (sorry)?" as he would say "be' ah".

An easier one: why can not a foreign person pronounce the sounds of the language exactly like the native people of that language? It's typical. Even stereotypical. Russians can't say the letter w in English: one (said "wane"), water, would, world.. what do they put there instead? They use the letter V! Vane, vaterrrr, vuuLLd, veerrrLLd is what I can do to make you remember a Russian accent. Some can say: I already knew it, other can wonder: why does it happen? Have you ever tried to imitate an accent? What's the main thing about it? To a German accent: "Ai'LL tRRai tu du sohmseen betaah": the strong -r realisations, the non-realisation of the -th sounds like -ð, but like -s, or -z, or -f or -d, which occurs in French accents too, and what about the melody in the Italian accent, or the shaking-head English of the Japanese, or Chinese? Those are stereotypes, of course. It's impossible, and I would say stupid, I mean, stewpid, to generalize the speech of so many people in a few ignorant "rules" or standards. But it does happen, and we can't deny that many people speak in a certain way it is possible to identify a few or many standards, if it was not possible, stereotypes would not exist. And the why is: influence.

Who gets this influence? People who speak English with an accent which differs from the Original English (I would call it Original English to make it simple, though many linguists would disagree with this term), and non-native English speaking people. In other words, evrybaddie. Ops, everybody.

"Everyone speaks with an accent. You may speak English with an accent from a different region in the United States (or England). You may speak English with an accent because English is not your first language. You may speak French with an English accent. In our world today, people move from state to state and from country to country. One thing that we take with us no matter where we move is our accent." available at: <http://www.asha.org> accessed in 5/7/2011; my parenthesis.

"An accent is a way that a person or large group of people (generally grouped by a nationality or specific area) speak. Despite the language, there may be some variation in how that group speaks. Those could be through long / short vowels, speed of talking, intonation, diction, stress syllables, formality when speaking to others, pitch, and slang." available at: <http://www.asha.org> accessed in 5/7/2011

" Scots was the official state language of Scotland for around 400 years in the Middle Ages. It lost its importance due to major political events in the 17th century. After a long absence, it is now finding a place again in Scottish education. [...] 'In 1603, James VI of Scotland assumed the throne of England, uniting the two kingdoms. And in 1611, James authorised a translation of the Bible to be read by all his subjects in English. The removal of the court from Edinburgh to London and the sanctioning of English as the language of worship was a double blow to the fortunes of Scots. The language lost its status in Scotland. English was the new language of power and poetry and over time the ruling and professional classes did their best to forget their Scots tongue. The 18th-century philosopher David Hume famously sought to edit out what he called his ‘Scotticisms’, or Scots words and expressions, from his writing in English." available at: <http://www.ltscotland.org.uk/knowledgeoflanguage/scots/introducingscots/history/index.asp> accessed in 5/7/2011; 'my underline

"Danish : Jeg kender ham ikke; Scots : A dinna ken him; English : I don't know him; Dutch: Ik ken hem niet." available at: '<wordreference.com> accessed in 5/7/2011;

That is why we have impregned in the Gaelic language English-loan words like -briecfasta and -doras. I am sure you can guess what they mean even if you have never heard about Gaelic before, and I tell you that it's the language that was spoken for the majority of the people in Ireland before. And guess what? It also received the influences I am talking about, not only in the epoque the British came there, but also in its formation: Celts came with the language I'd say "pure", the Viking came with their Scandinavian traces, the Anglo-Normans with their French bagagge, so we had the Irish language before the English influence.

"That English has had a considerable influence on the structure of Irish is only to be expected given the dominant position of English in Ireland since at least the mid 19th century (Stenson 1991, 1993)."

"One measure of the extent to which English words have been integrated into Irish is whether they can combine with Irish prefixes and suffixes. For instance, the augmentative prefix an-, found in native combinations like an-suimiúil ‘very interesting‘, an-bhródúil ‘very proud‘, is also found with many English words, e.g. an-funny (no lenition), an-weird. Sometimes, the English word occurs in combination with the prefix in one specific meaning from English, Bhí an-night againn san ostán ‘We had a great night (of entertainment) in the hotel‘, Bhí an-time againn ‘We had a great time’."

"On the level of syntax there is a strong influence of English, despite the typological differences between the two languages. The reason for this somewhat paradoxical situation is that there are certain structural parallels between Irish and English which facilitate the transfer of English patterns. English phrasal verbs and verbs with prepositional complements are particularly common in Irish (Doyle 2001a, 2001b, Veselinović 2006) as are direct translations of English idioms. These are usually translated word for word, something which is possible in quite a number of cases:" Bhí sí déanta suas mar cailleach. ‘She was done up as a witch.’

[was she done up as a witch]; Thóg sé tamall fada ceart go leor. ‘It took a long time sure enough.’[took it time long right enough]; Bhí orm súil ar an t-am a choinneáil. ‘I had to keep an eye on the time.’[was on-me eye on the time COMP keep]; Caithfidh tú d’intinn a dhéanamh suas. ‘You have to make your mind up.’[must you your mind COMP make up]. available at: <http://www.uni-due.de/DI/English_Influence.htm> accessed in 5/7/2011

“An early form of the Irish language was brought to bronze age Ireland and Britain by the iron age Celts, who inhabited Central Europe some three thousand years ago. The Celtic languages (which are a branch of the an "Indo-European" family of languages) consist of the' 'Continental' 'Celtic languages (consisting of Celtiberian, Gaulish, and Galatian), and the' 'Insular' 'Celtic languages of the so-called British Isles. This Insular group is further divided into the' ''Brythonic'' 'group, consisting of Cumbrian, Welsh, Cornish, and Breton of which only Welsh and Breton have survived into modern times, and the' 'Gaidhdelic (or Goidelic)' 'group of Scots Gaelic, Manx Gaelic, and Irish Gaelic (known in Ireland simply as Irish).”

[...]

“The' 'Viking' 'invasions between the eighth and tenth centuries A.D. left lasting traces on the culture and language of the population, and many typically Scandinavian words are found in modern Irish, in particular those relating to ships and navigation. The next settlers, the' 'Anglo-Normans' 'in the twelfth century, brought with them a French influence, most notably on the Irish literature of the period and especially noticeable in the southern dialects.'

[...]

During the period 1200-1600 Irish was the dominant language in the country, though some within the educated and aristocratic classes were bilingual.”

available at: <http://www.gaeilge.org/irish.html> accessed in 5/7/2011

or still...

"Irish has influenced English in some ways. Answering a question by repeating the subject and appropriate verb (am/are/is/was/were, has/have/had, do/does/did, will, etc) (e.g.”I am”, “He did”, “We do”) instead of “Yes” or “No” has a source in Irish, whose grammar dictates that yes/no questions be answered with the verb (e.g. “An deir sé? Deir sé.” “Does he speak? Yes.”) The non-standard “I do be” is based in Irish as well, whose non-copular verb “to be” has two present tenses, one for how things are – “I am at work” – and one for how things are frequently – “I am at work every day”, which in some parts of Ireland might be spoken as “I do be at work every day”, or even “I do be at work”, which differs from “I am at work” in that the former means “I’m regularly at work” and the latter means “I’m at work now”. Dropping “do/does” is also possible but rarer: “I be at work in the mornings”." available at: <irishenglish.com> accessed in 5/7/2011

"The influence of Irish on the way we speak English goes way beyond the odd loan-word being inyroduced into everyday speech. We often say things like "Have you any English?" instead of "Are you able to speak much English?"

Literally from the Irish "An bhfuil aon Béarla agat?" available at: <www.wordreference.com> accessed in 5/7/2011 In Irish, you have a language if you speak it.

Did you realize that the influences do exist even in languages that are "strong" today? In Portuguese, there are, if not a few, many French words, or words with French influence: boate (boîte); abajur (abbajour); buffet (buffet) etc; also English words like deletar (to delete), linkar (to link), feedback, feeling, and also German words make part of the language.

And what about foreign influences on the English language? Is the language of the Yankees a wall against influences? Of course not, and far from it. I'd say it receiveS much more influence than any other language.

Tycoon (Japanese), manager, bureau (French), ice, name (German), substitution; education, democracy, psycology (Latin and Greek); and those are only a few examples. There are hundreds or maybe thousands. Don't you believe? Check these:

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foreign_language_influences_in_English>

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_English_loanwords_by_country_or_language_of_origin>

<http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaidhlig/cananan/beurla/faclan.html>

Did you realize that there are (many) languages which were formed, or received strong influences in their formation? If not, here is another example:

"Scots is the closest sister language of English but it has plenty of European cousins. Bearing in mind its Germanic origins, it should come as no surprise that the German word for cow is kuh. Dutch, Frisian and Flemish also have a lot in common with Scots –kennen for to know (Dutch), twa for two (Frisian) and broek for trousers (Flemish).

And with a history interwoven with our neighbours across the North Sea, Scottish people already have a considerable knowledge of Scandinavian languages before opening a Danish, Norwegian or Swedish dictionary –hus for house (Danish), barn for child (Norwegian) and bra (pronounced braw) for good (Swedish)." available at: <http://www.ltscotland.org.uk/knowledgeoflanguage/scots/introducingscots/europe/index.asp> accessed in 5/7/2011

One living language influences other living language too (try to think how many English words 'entered' in your language if you are not a native-speaker, mostly the computing related words are a good example.)

With this, I want to show that influence exists and happens, and answer the most frequent asked question I get by people: "Of which language did you 'copy' it?"

"Vöxek is not a copy of any language existing today, or a copy of a language that existed in the past. It is a different language, with, yes, influences of the languages I used as basis. There are languages that influenced Vöxek that, maybe I don't and won't never know they exist or existed in the past."

_____________________________________________________________________________

Influences from other languages[]

OLD ENGLISH - "Old English (Ænglisc, Anglisc, Englisc) or Anglo-Saxon is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century. What survives through writing represents primarily the literary register of Anglo-Saxon." <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English> accessed in 5/7/2011; see also: <http://www.anglik.net/englishlanguagehistory.htm>

It is possible to say, in some ways, that the entire Vöxek language came from this old language, because if we stop to think about the number of foreign influences Ænglisc received on that time (remember I'm talking about a time around the 10th century), and the number of languages it influenced afterall, we can securely realize it can get the status as the "grandmother tongue" of great part of the languages spoken today:

"In the course of the Early Middle Ages, Old English assimilated some aspects of a few languages with which it came in contact, such as the two dialects of Old Norse from the contact with the Norsemen or "Danes" who by the late 9th century controlled large tracts of land in northern and eastern England which came to be known as the Danelaw." '<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English> accessed in 5/7/2011

"The second major source of loanwords to Old English were the Scandinavian words introduced during the Viking invasions of the 9th and 10th centuries. In addition to a great many place names, these consist mainly of items of basic vocabulary, and words concerned with particular administrative aspects of the Danelaw (that is, the area of land under Viking control, which included extensive holdings all along the eastern coast of England and Scotland)." 'available at <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English> accessed in 5/7/2011

As Latin is the major-ancestral (there were other influences, as the Classic Greek) language of Spanish, Portuguese and Italian, Old English is the major-ancestral (Old Norse was the other) language of Vöxek. It does not mean that you have to look up for Old English to learn Vöxek, as far as you do not need to learn Latin in order to learn French or Spanish. The influences were token "alive", which means that Vöxek, even though it has been born to this Old mother or grandmother language, it received direct influences, infuences of our time, of the languages alive today, not from the 10th century. This justifies that you don't even have to know what Old English was to its speakers to know something about or learn Vöxek. In the other hand, if we analyze only the phonology, forgetting, so briefly, the other components that make up Old English language, we can already realize how alive Old English is still being today, even after the Great Vowel Shift (transition from Middle to Modern English), and even being dead for centuries.

OLD NORSE - [...]"is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and inhabitants of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300." <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Norse> accessed in 5/7/2011

As commented above, Old English is the "mother-language" of many today-spoken languages. Old Norse is also one of those mothers. The above passage tells us that Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia. The most spoken languages in Scandinavia today are Norwegian (I am not considering the Nynorsk or the Bokmål variations being different languages, but just one.), Danish, Swedish, and maybe we could consider Icelandic and Faroese, even they are most spoken in their countries, not located in Scandinavia. Those are the languages that I took for influence to Vöxek, even knowing, as above explained, that these languages are derived from Old Norse.

"The modern descendants of the Old West Norse dialect are the West Scandinavian languages of Icelandic, Faroese, Norwegian and the extinct Norn language of the Orkney and the Shetland Islands; the descendants of the Old East Norse dialect are the East Scandinavian languages of Danish andSwedish. Norwegian is descended from Old West Norse, but over the centuries it has been heavily influenced by East Norse, particularly during the Denmark-Norway union."

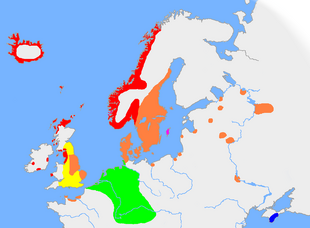

The picture below shows the areas where the languages were spoken in the 13th century.

The approximate extent of Old Norse and related languages in the early 10th century.

'thumb|left|384px|link='

MODERN ENGLISH - "Modern English is the form of the English language spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England, completed in roughly 1550." available at: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_English> accessed in 5/8/2011; It's the language you are reading now, the English you and the world speak today.

nouns, adjectives, verbal times in Old Vöxek, prepositions, grammar rules;

GERMAN - vocabularies, verbal times for the various past tense forms, prepositions, hard pronunciation, grammar, endings, numbers;

DUTCH - double-letters (ee; aa; oo; uu...), verbal times for the various past tense forms, pronunciation, formal way of speaking, verbs, pronouns(personal, reflexive, possessive);

DANISH - hard pronunciation, glottal stops, a voiced dental non-sibilant non-fricative letter or just "half d" as I like to call it (ð), made in a special way for Danish speakers, rather than the -th sound in -there, used in the English language; vocabularies, grammar, some letters in the alphabet, some numbers;

NORWEGIAN - as Norwegian and Danish are almost the same language, I can say the influences of both were almost the same, though Danish influenced the language most, since the first phase;

SWEDISH - vocabularies, endings, pronouns, -sj sound;

GREEK/LATIN - words that in English end with -tion are Latin/Greek, vocabularies

ITALIAN - endings - zione, vocabularies

POLISH/TURKISH - letters of the alphabet (with acute (visual changing): ex: ł, ś, ş, ç, etc), vocabularies in first phase and Early Old Vöxek;

FINNISH - endings, grammar (I explain what below);

IRISH GAELIC - sounds, writing system, diphthongs;

Phases of the language[]

Ancient Vöxek - it's the project itself, with totally arbitrary words created, with a confusing phonology and alphabet, with an intelligible grammar. The verbal times confused with themselves.

It has got a small Swedish influence, which can be noted in the pronoun "Jag" which last until Middle Vöxek, and -kwinë (from Swedish -kvinna), which is a newer word, a strong Polish influence with the letters of the alphabet, but not yet in the words, which were mostly created from English with a phonology which was close to the German one.

First phase - The words started to be created more systematically, but without much focus on the influence, they were still very arbitrary. The Polish influence in the words formation was strong, but not on the vocabularies, but the style of the words themselves. It was not rare to see English words written with Polish phonology and writing system.The first adjectives, nouns and verbs were created on this phase, and some of them last long, others, in the other hand, others were quickly abandoned, being replaced for more stylish ones, mostly coming from Danish. Great part of the grammar was created at this time, but it was less functional and simple. German words were very frequent: -zu, -mit, -niç (from German -nicht), -vom, kinden (from German -kindern), -du, -brijngen (from German -bringen), -släpten (from German -schlafen), -wÿssen (from German -weißen), -plazt, -alleune (from German -alein), -vehrspahrten (from German -vehrstehen), and the English ones too: -vlohr (from English -floor), -mohr (from English -more), -jester (from English -yesterday), -łeerhrt, after spelled -lørht (from English -world), -heezone, after spelled -høzøne (from English -reason), vijng (from English -thing), -schuud (from English -should), vëðë (from English -father) etc.

Early Old Vöxek - (also referred as Danish invasion) - as commented above, the words from Danish already existed in the first phase, like -gøren, -høren, -teulen (from Danish -talen), -honen, -brëuken (from Danish -har brugen til), -andre, skołe etc. I would say that Early Old Vöxek had two phases. The first phase of it didn't have a structured grammar, it worked somewhat like the English grammar, with German traces. Even, there were fully translated English expressions, as -drÿw me ijnsajn (from English -drive me crazy). In its second phase, there was an effourt to make a better structured grammar. Before that, a few lessons were created in order to keep the changes written, and those were full of new (and old) Danishisms: -wøden (from Danish -hvordan), -kömer (from Danish -kommer), -studeren (it was -studierten before), -tëk (from Old Norse -þakk (tak in Modern Danish), -ikke, -sagen (from Danish -sige), -vørste (from Danish -først), -til, -vorældren (from Danish -forældre) and hundreds of others.

Late Old Vöxek - the first structured grammar was created. The main thing about it was the creation of the two forms of speaking: separatiph (separative) and grøter (agglutinated), an idea I got from Finnish. Finnish is a language which has more than 2000 suffixes for its nouns, which can mean things you never imagined before. For instance .. for each change of the noun, there is one ending. Let's suppose that the ending coresponding to the preposition -with is -th. the grammar would tell me to say: "I mysisterth", meaning I am with my sister. If the light changes to red, you have a suffix, if the man passed the red light you have a suffix, if someone entered an open place there is a suffix, if one enters a closed place, other suffix. (I am exagerating, of course). And its order alters very much the meaning of the sentences. A small example:

Pete rakastaa Annaa. This is the normal word order, the same as in English.

- Annaa Pete rakastaa. This emphasizes the word Annaa: the object of Pete’s love is Anna, not someone else.

- Rakastaa Pete Annaa. This emphasizes the word rakastaa, and such a sentence might used as a response to some doubt about Pete’s love; so one might say it corresponds to Pete does love Anna.

- Pete Annaa rakastaa. This word order might be used, in conjunction with special stress on Pete in pronunciation, to emphasize that it is Pete and not someone else who loves Anna.

- Annaa rakastaa Pete. This might be used in a context where we mention some people and tell about each of them who loves them. So this roughly corresponds to the English sentence Anna is loved by Pete.

- Rakastaa Annaa Pete. This does not sound like a normal sentence, but it is quite understandable.

available at <http://www.cs.tut.fi/~jkorpela/finnish-intro.html> accessed in 5/8/2011

[]

Middle Vöxek - transition from Late Old Vöxek to Modern Vöxek. The last was still used informally, both Late Old Vöxek and Modern Vöxek coexisting. It is referred as the Dutch invasion too. It had already a structured grammar and a great amount of words. The work now was to remove so many Danish influences to let Dutch ones take place. A total reformulation was made, gender, number, pronouns, style of the nouns etc. The two phases coexisted, that is why I want to call it Middle Vöxek. Late Old Vöxek had got the status of informal language, while the Modern Vöxek had got the status of formal language that time.

Modern Vöxek - considered to be the formal way of speaking. At this time, there was an important idea of reformulation: the phonetics. A new alphabet was set, and new sounds from Dutch and Irish were introduced. A new writting system took place instead of the Danish-based one, and clusters and diphtongs from Irish were introduced. The vowel and consonant chart were created. Standard sounds were systematized, long sounds were introduced with the use of double letters, for instance -late, which became -laat. Diphtongues were introduced to avoid so many umlaut-letters, an old idea from German. Too many umlauts make the language seem to be very difficult while it is not. The Irish aspiration (-ch for example), eclipsis (-dt for example) and lenition (-mh for example) were added. A couple words from Welsh and Scottish Gaelic were also incorpored, but much more from Irish. Now new words were being created with those new influences.

Sounds of the language[]

Part 1 > Pure letters

Meaning of the arrows:

{C

{C

( → = tending to)

(← = or ) (depends on the speech varieties and the phase of the language

VOWEL SOUNDS - with the variations

CONSONANTAL SOUNDS - with the variations

Vowel and consonant charts are from the Old phase of the language.

Click the phonetic symbols inside the [ ] to be directed to its ample sound.

A a [ ɑ] → [a] - closed, extended, lips not rounded. Like -aw in Shaw. It is the sound of -á in Irish words like -álainn, -tá etc. (Connacht/Ulster dialects), but not long.

Æ æ [æ] - almost like the Danish -æ, but made lower in the mouth. It tends to substitute -ä [ɛ] and to be closer to this sound, rather than sound more like -a. It was evicted in Late Old Vöxek, but became strong again in Middle Vöxek and is still used.

Ä ä [ɛ] - open -eh sound like -a in "fast" (American accent) or "hähn" (German). It's an old letter, which does not appear in new creations anymore. In Early Old Vöxek, it appeared in words like -bähr (-trhögh after the Dutch invasion), ðär (now spelled -daar) etc.

Middle Vöxek Shifts and sounds transitions

Å å [ o] - very very closed -o, almost with the mouth closing, rounded. Like -å in Danish -forråde, but more rounded. Although in fast speech you will not have time to make it so closed, therefore, a glottal stop often follows it. It's an old letter, which came with the Danish invasion. It was strong for some time, and it also coexisted with -ò (same sound, other representation) after a reformulation in the alphabet (Early Old Vöxek). After it, it was also substituted for the French -eau. There were words which were never spelled with -å, like -speau, there were words which were spelled with -å and with ò, like -sålve, -sòlve; åsså, òsò (now -oos) but never with -eau, and there are words which were spelled only with -å, which still exists and were never written with -ò or -eau, like -årr, hårr, wårr...

B b [ b] - it's the -b in -boat.

C c [t͡s] - sound of -ts like Esperanto -scienco /st͡sient͡so/ or -z in German -zahl, magazin. There are now words with this letter anymore. Some of them lies in the First Phase like in -höce.

Ç ç [ ç] - like -ch in German -mädchen (palatal). Old letter, from Old Vöxek, which appeared in words like -niç, -køniç, and last until Late Old Vöxek with words like -wraçten (After dutch invasion: -skreeuwen).

D d [ d] ← [dʰ] ← [ʔ] ← [ʔ:] ← [ɾ] - a little aspirated, like -dz but very soft if forming syllabes. The Brittish people use this -d. When it is alone, it is not so aspirated, becoming a normal -d. It can also be very soft, sounding like a tap-r like in American words like -body, -middle or t in -bottle, -myrtle when placed before opened vowels. Sometimes it can be "hidding"a soft glottal stop or a total glottal stop. For example, when it is in the -nd combination before an opened vowel, it configures a total glottal stop: Slender /'slen-ʔ: ɐ/ = slender; Romnder /ʀɔmn-ʔ: ɐ/= spider

When -nd alone, it is a normal stop, usually making a smal nasalization in the last vowel: Strand / 'stʰʀɑnʔ /= beach

These changes in the sounds (called variations) are related to the time/duration of the speech. If you talk very fast, you will not have time to make the sound as the pattern. It takes (a little, okay, but it influences on the speech) time to position the tongue in the correct place for all sounds when they're much far in the mouth. If you talk slowly, you will have time, then you should make them correctly (following the pattern.)

Ð ð [ ð] - when forming syllabes is like -th in the English word that or -maður (Icelandic).. When alone is the middle sound of -t and -th (voiced). Like -med, hvid (Danish). It is possible to write -dh in the word, though the pattern is ð. It came in the Danish invasion, more from Faroese and Icelandic than from Danish itself. It didn't have a wide use, only in a few words. It's still very rare, and tends to disappear. It's a trace from Old Norse.

E e [ e] → [ə] - closed e sound like e in -hela (Swedish); say, day, stay (English) - without the trace of ee sound in the end. mij, vijf, schrijven (Dutch - more open, not -æi)

Ë ë [ aʰ] - open -a sound like in -height, with a bit more air. Rarely used until Middle Vöxek, still rare in Modern Vöxek, but it does not tend to disappear. New words may receive this letter. It comes with an aspitation after it, just like the Irish pronounce the letter -a sometimes in English like -fat

F f [ f] - normal -f sound but it just can come alone in the word. Like -dasph, never like in -fad. Always written -ph in the word. A variation for this sound is the unvoiced bilabial fricative. It's very rare. In Modern Vöxek only a few words still insist on having this fricative, though it may be replaced by -bh or other aspiration in following phases.

G g [ɡ] ← [x] - velar sound of g in -garçon (French); forget. It can also be affricated (very rare) when placed after closed vowels. It is almost completely extinguished, though it was very common in Old Vöxek. Only it's aspiration (gh) will appear frequently. Some old words like -gööben still holds it. It is rare but it does not tend to disappear shortly.

H h [ɦ] - almost same English voiceless fricative glottal sound. The difference is that this -h is murmured [voiced] in some accents. Ex.: Some Brazilian-Portugese dialects: -carro, -Marrocos, -garra.

Ħ ħ [x] - voiceless fricative velar sound. It is writen -gh in the word, like -ghedronken / 'xe-dʀɔn-ken / =drunk or -draghe / 'dʀɑ-xe / =silver. Very common in Modern Vöxek due to Irish influence on writing system and Dutch one in the phonetics.

I i [i] - i sound, but not the short-i sound used in English in words like -bit or -sit. It is made upper in the mouth, more closed. Ex.: -beat; sleep. Only a few words still have this letter. It has suffered an centralization, and later became the English -i in -skirt, but written -ie, instead of just -i. Remaining words holding a frontal closed -i are to be restylished. Example of the change: winen > wiennen; wimer > wiemmer

Ï ï [äʏ] → [œy] - diphtonguized letter. It corresponds to a diphtong in Dutch, though it is not exactly the same thing. It will sound like -huis or -gebruiken. To make it clearer, try to figure out how rural (northern) Irish people would say words like -about, -now, -mouth. The Dutch form is just a variation, or allophone, which does not make any changes in understanding.

J j [ʝ] - voiced palatal fricative. Like in Dutch -jaar or in German -junge, but with more frication.You should close the palate a bit more. It was more common in Early Old Vöxek, therefore it's not anymore.

K k [k] - normal -k velar sound. It may come with some aspiration sometimes. There is no -ck combination.

L l [l] - It was like German and Danish. You should close all the channel. It was not the English -l. Ex.: -alt, -eller, -lössen. After the Dutch invasion, it became [ɫ] - pharyngeal or maybe uvular -l sound, alone is the same -l in -bulb, -will. It is more close the Dutch -l like in -altijd, volk, maal.

In some areas, the Dutch -l stands almost for an -u, and in others, closed like German, forming another syllable in the following articulation. Same occurs with the -r. This letter is more like when it stands for an -u, though it is different. This is called cluster. Imagine how Irish and maybe some Scottish people say -film, farm, Cork. It's like fillim, farrim, Corrik.

In some words, it sounds like the Irish pronunciation.

M m [m] - normal -m in -merge.

N n [n] - normal -n. It can also be palatalized if doubled, basically after/before -u, -i or -ui. Like in the word -fhuinneog / 'ŭiɲ-ʔ-ɲiəg / =window. Don't expect to find a lot of palatalizations, because they won't occurr so frequently. Post Modern Vöxek has mantained this feature: heonnt /hɞɲ-ʔ-ɲt/ (it was hönd before).

O o [ɔ] - open -o sound like -hot but with lips rounded, made upper in the mouth. Check table.

Ö ö [ɘ] ← [ɘʊ] - it is hard to explain. I am not even sure about the correct IPA for it. It sound like -ɘ. Notice that it is not the Schwa. A closer example are words in Brazilian-Portuguese with have the -â character, but it is not nazalized as they do. If you know the character, try to say it with a pure sound (without nazalization), like in words as -elegância, -âncora, lâmpada. The other possibility [ɘʊ] is only used if the -ö is in the end of a syllable. Compare:

höce: hö - ce / 'ɦɘʊ - tse /=house

hösweerk: hös - weerk / ɦɘs - vĕiɹk /=homework

Ø ø [ø] - umlaut -o/e (lips rounded pronouncing -eh). Same IPA sound. Came with Danish invasion, now changed to -oe since the early phase of Modern Vöxek. It has suffered a centralisation too, though both pronunciations are allophones.

P p [p] - normal -p, a little bit aspirated.

R r [ʀ] ← [ʁ] ← [ɹ] ← [ɣ] ← [r] ← [ɰ] - very complex letter (it can get many sounds). Forming syllables (initial position) with -a, -å, -o, -u, -ö, -ë it is like German (uvular trill). Forming syllabes with -i, -oi, -io it is trilled in the alveoles (soft). With the remaining consonants, it is mostly a voiced velar fricative, though you can make it uvular if you get time. Inside of a word it is mostly uvular, but it can also be palatalized and velarized depending on the production of the preceding/following sounds. The same occurs in the end, depending on the sounds around it. The last IPA sound written above corresponds to a velar aproximant, used when the -r is before a long vowel. Ex: huurs. In this case, the variation is the English -r, mostly used in Vöxek after -aa and -oo, although it can be used after any long vowel. It can also grow the level of speed in a vowel, somewhat like occurs in British English words like -first, fair, cure.

These changes in the sounds (called variations) are related to the time/duration of the speech. If you talk very fast, you will not have time to make the sound as the pattern. It takes (a little, okay, but it influences on the speech) time position the tongue in all sounds when they're much far in the mouth. If you talk slowly, then you should make them correctly (following the pattern.)

Ŕ ŕ [ɹ] ← [r] - represented by -rh, same English -r. It can suffer a retraction. If you see the combination -rh, you cannot make it with your throat like a normal -r allows. Try the English -r or a thrilled -r. Check table.

S s [s] - normal -s sound like in -soup. Between vowels it has a soft -z sound, very soft. It can be retracted in some cases. When it is followed by central mid-open vowels in general, it gets a retraction accordingly to the last sound's position. Example in which the s suffers retraction because of the vowel: -ies. Check table.

Ş ş [ʃ] - like English -sh. Normally changed by the combination -skj. It's an old Danish trace, dead since Middle Vöxek.

Ś ś [tʃ] - like -ch in -cheese, -check, or -tj in Danish. Usually written -tskj. It's an old Danish trace, dead since Middle Vöxek.

T t [ t] ← [tʰ] ← [ʔ] ← [ʔ:] ← [ɾ] - aspirated -t, but softer than c. Don't make confusion with it. The letter c does not even appear anymore.

It can be replaced by a stød (glottal stop) in some cases or be an soft Spanish r (tap), as in american-English -better, -water. See [d].

These changes in the sounds (called variations) are related to the time/duration of the speech. If you talk very fast, you will not have time to make the sound as the pattern. It takes (a little, okay, but it influences on the speech) time position the tongue in all sounds when they're much far in the mouth. If you talk slowly, then you should make them correctly (following the pattern.)

Ŧ ŧ [ θ] - Like -th in English with or think.It is possible to write -th in the word, though the pattern is ŧ. It appears in a very reduced number of words, it is a trace from Old Norse which tends to disappear completely.

U u [u] - since the first phase until Middle Vöxek it was like -oo in -foot but made upper in the mouth, or Irish -ú. Check table. It became [ʏ] in Modern Vöxek because of the Dutch invasion.

Ü ü [y] → [ʏ] - umlaut (u/i). It was usually written -y. It does not exist anymore. The sound which remained from Early Old Vöxek is [y:], now represented by -uu.

V v [f] - just like -f, but for forming syllabes. Ex. -viertel (¼ - German), -vijf (5 - Dutch).

In formal speech this can sound as a soft -w (look below), as some Dutch people make with their -v in -voor, -vader in some dialects. This change is rare.

W w [v] ← [ʋ] → [β] ← [ⱱ] - like -v in -have or -w in German -wohnen if forming syllabes alone.

It is like -waar in Belgian-Dutch (Vlaams) if between vowels, a labial tap if the last vowel is more open. Hard -v sound between vowels is done by using the -bh combination. Alone in final position, it is just a soft labialization, which can be hardened if -mh is used. Like in -ðrhouwmh.

X x [k͡s] - Like -ks. Old letter, there are no words with -x anymore. As the name of the language is old, it is still spelled with -x.

Y y [ d͡ʒ] - Same -j in English -joke, -jaguar, -jerk. It was also a vowel (ü) during Old Vöxek period. There are only a small amount of words which are still spelled with y.

Ÿ ÿ [ai] - sound of -ai like in German -keine. Never used before -n, at the beginning and end of the word, being replaced by -ej. It was never very much used, it last until Middle Vöxek and it tends to disappear, though Modern and Post Modern Vöxek still keeps it. The most used word spelled with ÿ is mÿkket.

Z z [d͡z] - strong -dz sound. But in fast speech you will not have time to make it that strong. It was like that in Old Vöxek period, being replaced by the following in Middle Vöxek.

Ź ź [z] ← [ʐ] - same English -z sound in -crazy. The variation for this sound is the Dutch production in -zijn; which is a bit retracted. It's not written ź, though it was before, while -dz and -z sounds coexisted in Middle Vöxek.

Part 2 > Letters which suffer some konsonantal aspirazione.

It means some changing in the pronunciation. The tongue would be more relaxed.

bh [v] - it is used for making the hard -v sound between vowels, instead of representing -ʋ, which would happen if the letter -w was used.

ch [c] - It is a very soft sound made in the palate. Since it is plosive, it sounds like a -k, therefore it's very soft and retracted. Click the IPA symbol and listen to it.

fh [---] - it doesn't represent any sound. It is used when the word starts with a diphtong that represents one unique sound and in words with more than 1 syllable.. Example: fhoirëst /'ʉ -ʀaʰst/ =forest;

jh [ɟ] - the voiced combination for ch. In words like -Gaeilge. It exists, but there are not words with this sound yet.

mh [ʋˠ] → [βˠ] - It is just a velar -ʋ sound (more approximant than fricative), also with a glottal variation which occurs in words like -ghrouwmharh / 'xɹau-βˠəɹ / =above average growth

It correspond to a hard final labialisation too, when it's after a triptongue. It can also be approximant, depending on the context.

sh [ħ] - it is a pharyngeal sound, not very used around the European Community and not in Vöxek too.

nn [ɲ] - more Irish things. It is like Portuguese -nh in caminhão or Irish -nn in bhfuinneog. Palatal-nasal realisation (1) followed by a glottal stop and another palatal-nasal realisation (2).

Part 3 > Diphtongs

>> Which represent a single vowel sound

io [ɨ] - You must should it on the audio sample by clicking in the symbol. It is the Swedish -i sound. Example: fhiomhont / 'ɨvˠɔnt / =night (Modern word, spelled -nieght too).

io [ʉ] - it is the sound above but with lips more rounded. Example: fhoirëst / 'ʉ -ʀaʰst/ =forest;

eo [ɞ] - it is the /ɜ/ sound but with lips more rounded. It is not a common vowel because it is not completely voiced. You must interrupt a little the airflow in the glottis when pronouncing it. Example: trouwmheor / 'trˠau-βˠɞrˠ / =thunder;

oe [œ] - the ɛ sound, but with lips more rounded. Example: moelk / 'mœlk / =milk;

This is a good example to remember the sound of -l and -ł as described above. In Old Vöxek, that -l would sound like the German -l in -los, while in Modern Vöxek will sound like -heel in Dutch.

ie [ɪ] - the English -i sound in -bit, -fit;

ea [ɜ:] - long /ɜ/ sound, not rounded. Example: learskj / 'lɜ:ɰʃ / =deep or gheleardt / 'xe-lɜ:ɰʔdt / =learned.

-en (end of word) [ə] - it is the Schwa in words like -international or -intermediate. Only used in fast speech. Example: kenen / 'kĕin-ʔ-nə / =to know

>Which represents a long vowel

aa [ɑ:] ←[əa] - no secrets until the late phase of Modern Vöxek. It was just to make the -ɑ sound bit longer. Example: spraken / 'spʁɑ: -ken / =to speak; but after in Modern Vöxek you should add a schwa there: staark / stəaɰk /;

åå [o:] - now making the o sound longer; Example: iblåån / i-'blo:n / =sometimes/occasionally. It do not exist anymore;

ij [i:] - same above, but for i sound. Example: hyveij / 'hy-fe-i: / =vagina; died in Middle Vöxek

oo [o:] - same, but for o. Example: joortskjen / 'ʝɔ:ɰ -tʃen / =see you later; It was ɔ: before.

uu [u:] ←[ʏ:] - now for u. Example: huurs / 'hu:ɰs / =horse. It's now [ʏ:] in -buurt / bʏ:ɰt /;

>Other diphtongs

>>Schwa-vization

ëa [aʰə] - there are not many things to explain here. I will follow with examples: skjmëat / 'ʃmaʰət / =smart

ia/eo [iə] - Example: ghrian / 'xʀiən / or / 'xɹiən / =sun

oa [ɔə] - Example: loan / 'lɔən / =loan

ua [uə] - Example: ghruainn / 'xʀuəiɲ-ʔ-ɲ / or / 'xɹuəiɲ-ʔ-ɲ / =green

>>With e ae [ɑe] - Example: Shaen / 'ħɑen / =proper name

ëe [aʰe] - Example: hëe / 'haʰe / =here

ue [ue] - Example: huerrk / 'huehk / =little horse

>>With i

ai [ɑi] - Example: domhaiŧ / dɔ -'vˠɑiθ / =very good

ei [ei] - Example: eirskj / 'eiɹəʃ / =Irish

ui [ŭi̘] - Example: sjuimmen / 'ɧŭim-ʔ-men / =to swim

>>With u

au [ɑu] - Example: Rauph / 'ʀɑuf / =proper name

eu [ɔi] - Example: teulen / 'tʰɔi-len / =to talk (Early Old Vöxek word)

èu [eu] - Example: skjèulen / 'ʃeu-len / =to get up (First Phase word)

iu [iu] - Example: semhiu / 'se-vˠiu / =lenition

ou [ɔu] - Example: kought / 'kɔuxt / =participle of cut

öu [ɘu] - Example: vröukyst / 'fʀɘu -kyst / =breakfast

>> Other

ee [ĕi(ʔ)] - Example: geebt / 'gĕibt / =participle of give or een / 'ĕi-ʔ-n / =indefinite article (a/an)

TRIPTONGS - QUADRIPTONGS

>Without final labialization

aai [ɑ:i] - Example: klaaim / 'kʰlɑ:im / =claim

aau [ɑ:u] - Example: Klaaus / 'kʰlɑ:us / =proper name

eei [e:i] - Example: breeid / 'bɣe:id / =bread

eeu [e:u] - Example: leeuden / 'le:u-den / =climb a mountain

iju [i:u] - Example:

ieu [ɪu] - Example:

oou [o:u] - Example: woounen / 'vo:u-nen / =to live

> With final labialization

aauw [ɑ:uʋ] - Example: laauw / 'lɑ:uʋ / =law

eeuw [eiuʋ] - Example: leeuw / 'leiuʋ / =lion

ieuw [ɪuʋ] - Example: nieuws / 'nɪuʋs / =news

ööuw [ɘ:uʋ] - lööuw / 'lɘ:uʋ / = low (with more emphazis)

> Others

ouw [au] - rhouw / 'ɹau / =row

DEN NÖRGEN å NÖRGENNE (The numbers)

Vom 1 til 10⁶

This table is from Late Old Vöxek starting Middle Vöxek

| 1 - ejn | 11- elve | 21 - tårrer ejn | 40 - vierter | 200 - tår hunters | 900 - wöld hunters | 100.000 - hunter toisenden | |||

| 2 - tår | 12 - tolw | 22 - tårrer tår | 50 - vemser | 201 - tår hunters ejn | 1000 - (ejn) toisend | 100.001 - hunter toisenden ejn | |||

| 3 - tre | 13 - drögen | 23 - tårrer tre | 60 - se(e)pser | 210 - tår hunters des | 1001 - toisend ejn | 100.011 - hunter toisenden elve | |||

| 4 - viert | 14 - vierten | 24 - tårrer viert | 70 - se(e)tter | 211 - tår hunters elve | 1010 - toisend des | 100.111 - hunter toisenden hunter elve | |||

| 5 - vems | 15 - vemsen | 25 - tårrer vems | 80 - åtter | 300 - tre hunters | 1100 - toisend hunter | 101.111 - hunter ejn toisenden hunter elve | |||

| 6 - se(e)ps | 16 - se(e)psen | 26 - tårrer se(e)ps | 90 - wölder | 400 - viert hunters | 1110 - toisend (ejn) hunter (en) des | 111.111 - hunter elve toisenden hunter elve | |||

| 7 - se(e)t | 17 - se(e)tten | 27 - tårrer se(e)t | 100 - (ejn) hunter | 500 - vems hunters | 1111 - toisend (ejn) hunter (en) elve | 354.491- tre huntern vemser vier toisenden vier hunters wölder ejn | |||

| 8 - åtte | 18 - åtten | 28 - tårrer åtte | 101 - hunter ejn | 600 - se(e)ps hunters | 2000 - tår toisenden | 1.000.000 - (ejn) milione | |||

| 9 - wöld | 19 - wölden | 29 - tårrer wöld | 110 - hunter des | 700 - se(e)t hunters | 3000 - tre toisenden | 2.000.000 - tår milionen | |||

| 10 - des | 20 - tårer | 30 - dröger | 111 - hunter elve | 800 - åtte hunters | 4000 - viert toisenden | 10.000.000 - (ejn) miliarde |

First Grammar (Late Old Vöxek)[]

As I said, it has got two forms to write. Separatif and Grøter. It means the words get some changes in the structure. Ex.:

> Grøter form can "compact" articles, prepositions or everything that has some influence in the noun.

The sentence order in Present Tense is SVO (Subject-Verb-Object)I will represent separatif for S and grøter for G.{C}Ex.: Jag her een hönd (S)

Jag her höndde (G) {C}Both meaning I have a dog

For past tenses (formed with the verb -to have) the order depends on the time that passes from the time of speaking.

Subject - Verb hagen (to have) in the present tense - object - participle verb

JAG | HER | EEN HÖND | SET

(I saw a dog) or I have a dog seen

Subject - hagen - participle verb - object JAG | HER | SAGT | DEJ

(I have told you)

Sample text & more Late Old Vöxek grammar[]

{C}THIS IS A SIMPLE TEXT IN WHICH EVERYTHING HAPPENS ON THE PAST. IT IS IN THE SEPARATIPH INFORMAL FORM

Dét wer dét ......

Jester her een serr hanöf kwijnis með heare vamilie til de SkjopCentre gørt. Hear her i een störh een teu set. Hear her an heare mædre spørgt whis hear kune dat teu haggen.

De mædre her "jë" sagt en her dét keuvet. De kwijnis her står birkömt, så ðem her til hoom gørt.

THE SAME TEXT IN GRØTER FORM

Dét wer dét........

Jester her serr hanöf kwijnisse heare vamiliemeð SkjopCentret tilgørt. Hear her störhŕem teutte set. Hear her heare mædrem spørgt whis hear kune teutte haggen.

Mædret her "jë" sagt en her dét keuvet. Kwijnsse her står birkömt, så ðem här hoom tilgørt.

See the difference? The text can be littler and without little words like prepositions and articles.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Pronouns[]

In Vöxek, to express respect for someone is easy. It is just to use the correct pronoun and forms related to it.

INFORMAL

Jag - I

Du - You

Heu/Har/Dét - He/She/It

________________________

Wi - We

Dun - You (plural)

Ðem - They

Verbs

In Vöxek, the verbs have a particularity. They have plural form (!) Yes, thats it. If the verb is used with 1st, 2nd or 3rd person/plural and if it is regular, it goes to its plural form.

Infinitive -> termination is unique, and correspond to the regular plural form: -en

Ex.: honen (to eat) >> radical: -hon ; ending: - en (to eat)

høren (to hear) >> radical: -hør ; ending: -en (to hear)

yorten (to think) >> radical: -yort ; ending: -en (to think)

Also, there is a form to express infinitive, used in some grammar parts i'll explain later.

It is by adding the word -ät before the verb and removing the -en

ät hon

ät hør

ät yort

PRESENT TENSE

Add -er to singular, so we have (Informal) > Jag, Du, Heu/Har/Dèt > honer/hører/yorter.

The other will be like the infinitive (plural).

PAST TENSE

It is like examples in the beginning, with the verb -to have

TO HAVE = HAGGEN (irregular)

Jag her

Du her

Heu/Har/Dèt her

Wi här

Dun här

Ðem här

To the past tense (something that has finished), -hagen is conjugated in the present+verb participle

As I used singular examples above, now I use plural form.

>> Ðem här dét [jädt] sagt

(They said it or "They have it [already] said")

To express something that still happen, the order changes:

>> Ðem här sagt dèt

(They have been saying it or "They have said it")

Note the difference:

Ðem här dét sagt (finished)

Ðem här sagt dét (still in progress)

Just the order can tell you the difference. The words are the same (!)

To express things like -could, -would etc there are some words, but there is also a verbal time called -past vutur- that (I think) English does not have.

Basically, could = kune or kåd (it depends on where it is placed) and would = wune or wud

FUTURE

This can be simple for Germanic languages speakers, because future is done by adding some futural word. Ex.: German: werden; Danish/Norwegian: skal ; Swedish: ska ; English: will etc

Formula: Subject + wi l+ ät + verb without -en + verb + object

Ex.: (S) Jag wil ät se een ønsk

(G) Jag wil ät se ønskke

There are more types of future, as happens to the past. I won't put here because its more complex. Free to message me, I can send my PowerPoints explanations.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Nouns[]

As my personal opinion, I HATE male/female atribuitions for things. So I started to think about an structurated gender formation. Structurated doesn't mean difficult. By the way, it is the simpler one I know.

1. Articles (I hate them)

As great part of Germanic languages have them, so Vöxek has them.

Before talking about articles, I have to explain the genders. In Vöxek there are 4 genders for the nouns, and for your pleasure, it does not have anything to do with the sex of the things.

The genders are the following:

KOME GENDRE ; ENKER GENRE ; NEUTRE GENDRE [divided]> käse 1 ; käse 2

Don't be scared, these are just the names. We are going to see how easy they are.

>>>

Kome separatiph artikelen (Kome separative articles)

Neutre1 separatiph artikelen (Neuter1 separative articles)

Singular Plural

DE Definited (DEN) [not necessary]

EEN Indefinited ----

Ex: De sÿne er am de strøde

(The sign is in the road)

Heute hër jag een stør huurs set.

(Today I saw a big horse)

________________________________________

Komen grøter artikelen (Komen aglutinated articles)

Neuter1 grøter artikelen (Neutre1 aglutinated articles)

(ADD TO THE END)

Singular Plural

T Definited ----

R Indefinited ----

Ex.: Höcet er stør, abst bijet er glið

(The house is big, but the city is little) - ___________________________________________________________________________________________

ALWAYS THE PLURAL OF THE NOUNS ARE DONE BY ADDING -N OR -EN TO THE END

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Enken separatif artikelen (Enken separative articles)

Neutre2 separatif artikelen (Neutre2 separative articles)

Singular Plural

ET / DE Definited (DEN) [not necessary]

EEN Indefinited ----

>> ET/DE mean the same thing. The articulation of ET in those cases is more easy, but using DE is not wrong.

Ex.: Et ayer er stør.

(The lamp is big)

Et ønst är ruug, abst et andre i är det ikke. (A jaguar is vierce, but the other one is not)

Enken grøter artikelen (Enken aglutinated articles)

Neutre 2 grøter artikelen (Neutre2 aglutinated articles)

Singular Plural

double end letter + E Definited (Double end letter + EN) [not necessary]

double end letter + ER Indefinited ----

Kome words are called "K.E." words. By this name, you can always infer that a kome word will start by a consonant and end in a vowel;

- Enker words are called "E.R." words. By this name, you can always infer that a enker word will start by a vowel and end in a consonant;

- Neutre käse 1 is when the word is started and ended by a consonant;

- Neutre käse 2 is when the word is started and ended by a vowel;

Finally I am going to write little fool history, "grøtered". I wont mark the grøtered prepositions. Just see the articles. Dét wer dét ... Kwijn ner hÿsset Johann. Heu her kruugge nærlæpht, en her gehöt een gelant åp gøren ðär. Som'dëgh, Johann kune ikke warrten mörr timer. Heu er kruugge tilgørt. ... Heu her wålket .. äfterlederet ijnteressanten vijngenvor.. Heu leder arönd .. Så står, PLÖSLIKT, Johann se kinor! - Dét er såå ruug!" - Heu her yortet. Kinor her hunen heuvör skjtërktet. Plöslikt andre timer re, kinor her STØR gesjwijndskÿtte hapht. Johann her serr väst tretam apgørt. Lend de vortæler ðët Johann her ikke dungørt, en her ðär døert.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Middle Vöxek Grammar[]

{C}Middle Vöxek grammar is a mixture of what Vöxek had been until the Late Old phase with new Dutch traces, which were introduced at that time. Five new basic lessons were created in order to show and keep record of the new changes. This grammar had got a number of problems due to the subbit transition from the Danish system to the Dutch system, which includes also restylization of the words, rather than only grammar changes. Before the total structuration of the new phase, Middle Vöxek was something working "without a goal". It was not possible to create a word following a standard without a standard! Then, as I explained, new phonetics were created and adapted to the current alphabet, the system of words was standartized to something close to the Dutch writing system, without forgetting, of course, of the Irish influence, however not as strong as the Dutch one. Here it goes a text from the very beginning of the Middle phase. I'll be commenting in order to show what changes have been made. Other important thing is that at that time, the "new language" had got the status of formal language, while the "Danishised" language served as informal language. The two Old and Modern phases coexisted in the called 'Middle Vöxek phase'.

Here is the text. it's a copy of a newspaper news. I will not work with the translation since it's not the focus. Red words were brand new words, while the blue ones are very very old words. Unmarked words are mostly from Latin/Greek which have their compostition standard and have never been changed, apart of only minor phonetics corrections.

Ekonomíe: Bankken öpen dörren voor ijnternazíonalen transazíonen

Dét heebt jester ben, wen heebben de administrazíone ghroep of de Centrale Bank de autorisazíone vergööbt.

De präsident met de reste of de ghroep verwoonden ðët dét ies tijd voor een nÿe ekonomíe. En dét ies wat heebben ðee ghezeght.

Aphter de krisis, wen de Bank heebt –nee– voor de ijnternazíonalen kapitale ghezeght, met de víer ðët dét koodt de locale ekonomíe efvekten, de resultaat: de desizíone heebt wel verakseptet voor den léaders i den politiek en andre spesialisten.

Wee höpen ðët dét keen een gödt efvekt te haggen en ðët dét keen de prosper ekonomíe throigh brengen.

Pronominal changes[]

{C}We are on the changes the pronominal system suffered on that phase. Let's compare them since the First Phase. The blank fields are to be filled soon as soon as I get access to old records.

Personal pronouns

| English | Ancient Vöxek | First phase | Early Old Vöxek | Late Old Vöxek | Early Middle Vöxek | Late Middle Vöxek | Modern Vöxek |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Jag | Jag | Jag | Jag | Eek | Eek | Eek |

| Thou | Du/Die | Du/Die | Du/Die | Du/Die | Du/Die | Du/Die | Du/Die |

| He/She/It/You | Heu/Har/Dèt/Won | Heu/Har/Dèt/Won | Heu/Han/Dét/Won | Heu/Hea/Dét | Hee/Zhee/Dét/Jy | Hee/Zhee/Dét/Jee | Hee/Zee/Dét/Jee |

| We | Jagen | Wi | Wi | Wi | Wee | Wee | Wee |

| Ye | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien | Dun/Dien |

| They/Yous | Ðem | Ðem | Ðem | Ðee | Ðee | Dee | Dee |

Possessive Pronouns

| English | Ancient Vöxek | First phase | Early Old Vöxek | Late Old Vöxek | Early Middle Vöxek | Late Middle Vöxek | Modern Vöxek |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My | myr | mir | mir | mir | mir | meer | meer |

| Thine | čehr | dir/dier | dir/dier | dir/dier | dir/dier | dir/dier | deer |

| His/Hers/Your | heur/ | heur/hare | heur/hear | heur/häre | heer/zheer/jeres | heer/zeer/jeer | |

| Our | wir | wir | wir | wir | weer | weer | |

| Yourse | dire/diere | dire/diere | dire/diere | ||||

| Their | ðeirh | ðeer | deer |

Prepositions[]

Now we are going to show the prepositions of the language. Only to remind you, a preposition is the word that shows relation between the elements of the sentence. E.g. with, about, to...

You should notice that the titles of the columns refer to the phases of the language.